Rites of Spring

by Marcus Speh

He noticed a short, strong white hair from his beard on his tongue and decided to not take it out but see what would happen. A moment later, a tiny bear emerged from the cave of his mouth, grabbed the hair and pulled it on his lap to play with it. It was a furry sensation and the beginning of a long friendship with things coming out of his orifice. It made him want to dance, shave and dance in the rain shaved, to feel the water run over his clean cheeks and celebrate the connectedness of everything with everything else.

When we arrived at the Factory of Blind Infants very early in the morning, I saw the dog patrols. I lost a left foot on the first day and my right arm on the second. It didn't matter much because many of the Infants were incomplete. The games we played would have scared me before. Our stories revolved around limbs going around alone, begging their former owners to account for them. They mercilessly drilled what was left of us. After three months, I became an agent. I received a uniform and a gun and was declared ready for fieldwork. I learned that pride is a measure of loss and that there is no substitute for comradeship. I also learned that drugs could help me forget and that the loudest music comes from within, like water oozing from a stone.

Shaking and trembling. You imagine strident sounds made by strangers when their right hands are roasted over the fire by feds, who, a moment ago, had their hands down someone's pants because there was a tic toc and a tac tic coming from the aluminum-encased, sleek, ogre-sized detecting device radiating X-rays and dizzying your cells. Hymning slews. Working next to one of those machines might change your entire life: you must scan the perimeter, looping, with your especially developed anti-terrorist gaze, which will bring any offender to his knees, thereby creating another sound, the sound of a slowly keratinizing human. A final shaking, then silence.

Two leathery lovebirds set off to a jog through bewitching countryside. The stench from the fields was sharp and brought the animal out in Fred. His wife, Frieda, was belting along the dirt path despite her seventy-eight years. Fred's little Martian stirred merrily at the thought of the Venus trap between Frieda's legs. If the stars were aligned he might get lucky tonight he thought, all the way to his death that awaited him at the end of a seemingly infinite patch of bluebells, whose little heads were bobbing towards the place where Fred would fall and lie, his eye turned upward for as long as it took him to imbibe the beauty of the world for one last time and carry it wherever he'd be going, as alone as he hadn't been in half a century, while Frieda was storming ahead of him, her chin stuck out, a fighter to the last breath, an incandescent wife.

On the terrace outside of the commons stood a small bucket labelled ‘Nürnberger Würstchen', filled with green water. This is where students dropped their butts. It has been observed before: fags look like little musty, wiggling worms. What hasn't been said before is that here they actually were worms, with eerie eyes looking for idlers who were desperate enough to rescue them from the depth of destitude, drying and reusing the tobacco for roll-ups. A small contribution to a greener, better world. We called this place ‘Wormwood': it was easy to meet women there, hanging onto a stub, enabling and indulging addiction, slinking away from intimacy, eyes on the sausage.

Every morning this same set of choices: to eat or not to eat. To drink or not to drink. And how much. To shit or not to shit (no issue with volume there). To smoke or not to smoke (you still with me?) And moods! Go down in flames like a cleansing Easter fire or hold my breath indefinitely as we all learnt to do it, years at a time, swallowing sarcasm. Uncomfortable morning truth: I'm not a bird. I feel my bones, every one of them, nasty needles. I can fly but I must write my own wings first. Shall I touch the tender spot above my April blooming heart for help?

Fifteen monarch butterflies. Six and twenty snow drops. Ribbons with hearts on them. A dozen blown out eggs painted as Chinese policemen. Lost in last year's brown leaves: my glasses. Wandered off by themselves to look for the ridge of a nose that knows what it wants. Bunny-shaped mole on the skin on the back of my hand. Hundreds of white horse hairs clinging to my spring step. Greetings to all wayfaring strangers lost in elaborate egg hunts! Nothing can hold us back now: the best time of the year is upon us!

When Elmer found the hedgehog's diary one spring morning, he was a happy man. The text confirmed a number of his ideas about insectivorous mammals, shed a new light on the concept ‘pricks of conscience,' and contained as one major zoological behavioral sensation the information that the quarrel between foxes and hedgehogs was not a Darwinian necessity but was, in indubitable fact, a stage play, enacted continuously for entertainment, a choreography that brought, according to the hedgehog's copious notes, considerable pleasure to the ostensibly hunted.

He kept his pants on and made a stupid face, or so it seemed to him. There were no limits to the stupidity of faces on a man. He put it down to a lack of experience. Writing was so easy, too easy, but doing the right thing with a woman, a new woman, was difficult, too difficult. It required much more than imagining, which he was good at; it required dedication to something not just outside of himself but quite outside of his universe, something he could not own or imbibe or eat up. Still, he continued to bang his head against that particular wall, carried on pissing in that particular corner hoping for that particular look from her that would signal, once and for all: I'm yours.

Early in March, the snow had just melted, his glans showed white spots. “Probably a fungus,” his wife said, “perhaps you should wash there more often.” He imagined his penis as a rainbow-colored canvas where mischievous little devils played arty games, painting it this way or that. He might wake up tomorrow with a blue cock. Hypochondria did not set in, while only the tint changed. But the next morning, he found tiny feathers under his foreskin. That scared him. “Maybe angels visited you last night,” his wife suggested, trying to be helpful.

From my window I can see myself on the other side of the world, almost neckless, in a place where I don't have a shadow, where my fingers are fused to the keyboard forever and my tongue licks the screen hoping to pick up those very last pixels that escaped my wandering attention. There is no weather, only weariness. A crow comes to visit at odd times, dabbing my shoulder covered with corduroy. When spring arrives, I raise a storm in my palm and watch it listlessly, hoping for a merciful tide that sweeps me along into the wild, where I will live as a bear and cool my paws in the sunny water. I promise.

|

35

favs |

3703 views

68 comments |

1281 words

All rights reserved. |

Author's Note

Published (as Finnegan Flawnt) in > kill author issue seven ("Flannery O'Connor") together with a recording.

Listed among the storySouth Million Writers Award Notable Stories of 2010.

This is one of the 80 stories in my collection “Thank You for Your Sperm” (MadHat Press, 2013).

It made him want to shave and dance.

Amber Sparks wrote a lovely review of this piece: I printed and cut it in one hundred pieces and wove it into my morning prayer mat.

Spring: today's the day.

The bear, of course, has a special place in the city of Berlin where I live and work.

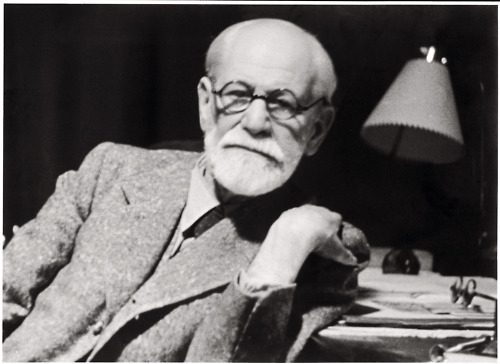

My daughter likes to draw covers for stories that have impressed her. This is one of the few of mine that does:

"Rites of Spring" cover by Lucia.

Update May 2011: grateful to Sam Rasnake for including this story as one of "10,000's favorite short fictions" in the company of wonderful writers such as James Robison, Julie Innis, Sara Lippman, Kathy Fish and others. I bow to them & to you.

Other stories by Marcus Speh

Tags

This story has no tags.

Groups

-

WAG (Writers Across Genres)

Public group33 members -

25+ Favorites

Public group28 members -

Second Tongue

Public group41 members

Goodness. The return of the prodigal - and with a bang and no whimper. This is a great form for this piece, Marcus.

Amazing imagery throughout -

"Two leathery lovebirds set off to a jog through bewitching countryside. The stench from the fields was sharp and brought the animal out in Fred. His wife, Frieda, was belting along the dirt path despite her seventy-eight years. Fred's little Martian stirred merrily at the thought of the Venus trap between Frieda's legs."

&

"Fifteen monarch butterflies. Six and twenty snow drops. Ribbons with hearts on them. A dozen blown out eggs painted as Chinese policemen. Lost in last year's brown leaves: my glasses."

&

"A crow comes to visit at odd times, dabbing my shoulder covered with corduroy. When spring arrives, I raise a storm in my palm and watch it listlessly, hoping for a merciful tide that sweeps me along into the wild, where I will live as a bear and cool my paws in the sunny water."

I don't know if you had Nijinsky's ballet Rite of Spring in mind at all here. And it doesn't really matter. It was in my head while I was reading.

One of your best pieces. Period.

thank you, sam, much appreciated. i got a lot of catching up to do around here! reading! commenting! and no shortage of projects. this seemed the right day to post this. indeed, i had stravinsky on my mind for this, all the way. and i do still like this a lot if i may say so. i think it's okay if we're in love with some of our work, esp when we forget most of it almost immediately.

Beautiful Marcus! so many wonderful lines... & it's my birthday so what a nice present ;) !And Bach's birthday too, so he will be happy...I like that you can dip in anytime and read out of order, just sink in and loose yourself.

That's just perfect then with your focus on Stravinsky. You're hearing the music, and I'm seeing the dance. That works.

And you should like this - It's a great piece.

Wonderful. And you save the best for last. What an image, the bear cooling his paws in the sunny water!

Big fav.

This is remarkable work, Marcus. And, it just dawned on me that I read it silently, to myself, in your voice. Which means, I suppose, that you've magnificently managed to capture that voice in text.

Really good to see you back here again, Marcus. You manage to breathe life into this place and it feels like a lot of people are bailing or on hiatus.

Hope you stick around for a while. This is a great piece, encyclopaedic in scope and laser sharp in delivery.

How do you do that?

enthusiastic fave

this is lots of fun. it's snowing here out of spite and this made me happy despite that. lots of lovely bits; i like the alliteration(s) and the play(s) with rhythms that is/are put into motion across the device. and stravinsky, which is always nice to have running through one's head.

*

you got me with the first little bear, Marcus,( Mon ours dit,"Salud.") and the second one to be was a bonus. But a lovely piece, the writing so free of visible constraints, the language spinning out its own stories, each so different, resolved, complete.

thank you, shelagh. happy birthday to you and many, many happy returns. what a great date to have been born. an honor to have you read this on yr bday.

thanks jack, thanks for reaffirming that image. i'm still chewing over it myself. we just had a sad death in berlin - knut the motherless polar bear died. berlin is actually bear-lin, the bear's the city's power animal.

hey, thanks susan. i'm just about to go up on stage to read out loud...new pieces though. this is very encouraging.

hi james, i appreciate your support & i'm glad to be back ... just in time for some spring feelings. about the pieces: these grew over a period of 9 months or so, one by one. 11 pieces for 2011 seems about right. looking forward to catch up on stuff!

stephen, beautiful, artful compliment, i appreciate it. hope the snow will melt soon where you are. daffodil time. my daughter (10) just approached me with a piece she has written...all the heroes and heroines have the names of flowers. except the father. he's called "devil". but he's quite the gentleman nevertheless. so much for spring feelings!

david, thanks. bears: see comment to jack swenson...special in berlin. "language spinning out its own stories" is well put, too. i feel seen, mate.

"Maybe Angels visited you last night" made me chuckle. So many great phrases here. Of course a fave.

Excellent, Marcus. What everyone else said. *

chris, gratefully acknowledged, your acknowledgement of that episode in particular. i do believe in guardian angels, of course.

appreciate it, christian!

@jack - about that berlin bear: "Zoo accused of contributing to Knut's death" - The Independent http://ind.pn/eyBVoK

This is beautiful. Must've read it three, four times since yesterday.

thank you, frankie, i appreciate it very much. when i read a piece more than one time, it usually changes for me-i generally take this to be a sign of good writing. like meeting the same person again and again as if s/he was another.

I think there is so much in this that I could not savor all of the complexity in one reading. I think 1. 8. and 11. are my favorite parts.

Pure Speh.

*

Oh, just read author note that it was written as FF> well, it's Pure Speh, too.

Absolutely stunning. Must read it a few more times. *

Wonderful.

*

..When we arrived at the Factory of Blind Infants very early in the morning, I saw the dog patrols.. as alone as he hadn't been in half a century, while Frieda was storming ahead of him, her chin stuck out, a fighter to the last breath, an incandescent wife..my tongue licks the screen hoping to pick up those very last pixels that escaped my wandering attention..I raise a storm in my palm and watch it listlessly, hoping for a merciful tide that sweeps me along into the wild, where I will live as a bear and cool my paws in the sunny water. I promise..marcus,my friend,this is amazing,inventive,fun and disturbingly beautiful writing.

My God.

It's like a thousand tiny switches just flipped on in my cerebral cortex.

Here's to Spring awakenings!

*

and RIP Knut...beloved by many schoolchildren in NH. :)

hey, susan, thank you. i'd have said it's pure flawnt but seeing how generously flawnt has transferred everything he was to speh, i concede your point.

lynn, bill, darryl and rene - thank you. let's do some good writing this spring! though as often when i post something that's been published already and over a year old on fictionaut, i feel awkward as in "what have i done lately?" ...

Marcus, Just read this through 2x and feel its one of those you can read through again and again like Joyce!! I would quote all of section 9 and then the rest.... Truly amazing!!! ******

aww, meg. joyce. that is exactly what he does to me. how sweet. must pour some cold water over my head now. cheerio.

This is some fantastically good writing. Your beautiful and surreal images perfectly captured the feeling of approaching spring.

"Every morning, the same set of choices..." Another winner. *

thank you, AG, for the lovely comment. time to take off that scarf and show us the whole pasquella...

thanks kim, as always, means a lot.

Marcus: as soon as spring decides to stick around Toronto, the scarf comes off!

A remarkable Spring sojourn from the mind of Speh!

Would like to read this to every Bern bear, and set them free to enjoy turquoise glacial waters of Brienzersee.

thank you, frank, much appreciated, especially since your comment is so lyrical and stirs my desire to travel far...enjoy your trip!

I read so much more of your work than I comment on, because I read it and there is so much to unpack and then I come back with the intention of saying something, but get lost again. This piece is no exception. Frank has the right word, remarkable.

well, lou, thank you for coming out here. your comment makes me realise, yet again, that all our little stories, even if they're gathered around a lit centre like fictionaut, are still out there all by themselves, wanting to be read. thanks!

11 great shorts!

Brilliant in the entire form: alone as each individual flash piece, or as the whole. Marcus you dazzle and enthrall me. I am so grateful that our paths cross in more than one place in this enormous universe. I am so fortunate. ****

thank you matthew, i appreciate it!

thanks robert, you make me blush and giggle. at the same time, it is worth pointing out as you have that this (world) is an enormous place and that we are fortunate and blessed to meet & read & comment upon each other's work. i don't take it for granted & i thank thee muchly.

"...and that the loudest music comes from within, like water oozing from a stone."

This is my favorite fictionaut piece to date.

It's brilliant.*

jen, thank you so much. that quote you picked...it resonates, for me, with your own writing. that's the music i hear when i read knox.

You had me from the first section on. I love every bit of this and how it makes me think and how it keeps me thinking and imagining, constantly. I like it that I read it twice and I gleaned even more from it upon a second read. I like it that my star will be number 25. I wish I could see a booklet of this interspersed with pictures but for now the virtual pictures of the colorful ballet dancers for Rites will do. I love Stravinksy. And here there is a bear and also a distinguished gentleman. This is, indeed, richly symphonic. Your friend - Meg *

hi meg, your comment makes me happy! it's too early in the morning for stravinsky right now but i do hope for a spring just as wild. "symphonic" is a wonderful compliment, thank you.

Bravo Marcus. Brilliant, inventive, and Yes, Symphonic indeed *!

marcelle, thank you very much - and a wonderful spring to you!

Really hit you, didn't it, the Berlin Spring!

I just love this, especially the sudden turns - like e.g. having a white hair in your beard immediately followed by a little bear from your mouth.

Only in this wonderfully crazy city. Or rather only in Marcus's delicious ravings?

thank you, luisa, and to you i say: enjoy spring in berlin, i know i will. walked around in it all morning!

Haven't been around here much, but this was a wonderful piece to come upon as I slowly return....

*****

i appreciate it cherise, and i'll keep one of those spring faves...cheerio!

yum.

thank you, jane, for the comment!

There's my favorite bear story!

I got a hair in the mouth a few days ago, and immediately thought of this story.

Love this: "It made him want to dance, shave and dance in the rain shaved, to feel the water run over his clean cheeks and celebrate the connectedness of everything with everything else."

In Norway we have a folk tale about a bear that comes to carry yo away from your everyday life.

This is a little like that bear. :)

Not much to say here that others haven't, but *.

thank you berit, i really appreciate it. i'd like to see that folk tale...love bears with all their fierceness,too.

thank you james!

Like a dream, interesting, soothing, disturbing, soothing again, and so on. Traumbilder.

thank you, beate, a fair number of these actually came to me as dream fragments and were spun from there...cheers!

Symphonic and filled with vivid images!

Every so often, I'll read a story that alters my perception to the point where I look up from it and everything looks weird, different. Marcus, your words twist up my ideas of things, take me on brain vacations.

*

Every piece drips off the page with colour, magic and the true glow of the imagination. Absolutely marvellous stuff!