Unnamed

by Steven Gowin

The child was delivered, set to breathing, and whisked away before Fae Anne could even catch a glimpse of her.

So functioned The Evangelical Lighthouse for Unwed Mothers just off the The Keosaqua Way, Des Moines, 1946… the maternity refuge for wayward girls from Iowa's tiny farms and hamlets.

The Lighthouse, built in the Craftsman style, comprised parallel wings with a courtyard between. At any season, the troubled unweds waited out their deliveries smoking and weeping in the shadows between the buildings.

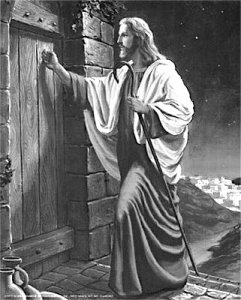

Although Jesus, knocking confidently on a wooden door, watched over Fae Anne from a reproduced painting above her cot, she slept poorly. The faucet in a miniature sink dripped constantly… hot water in summer and cold in winter. Down the hall, the girls queued for a single toilet; otherwise it was the bucket.

Such punition and everlasting shame, so claimed the Evangelicals and so Fae Anne understood, were those bad and unholy girls' merits for their terrible transgressions with men. No wonder the Evangelicals forbade the girls from naming their children.

Nevertheless, in utero, Fae Anne did name her child. At its birth, however, she'd refrained from calling out that name aloud.

![]()

When she'd returned from the Unweds, Fae Anne wanted to believe, and sometimes told the story that her baby's father had surely taken advantage of her, tricked her and run away, a Svengali and Casanova, this dark prairie Lothario.

In truth the papa, a boy of 20, had recently seen action in France. He and Fae Anne had spent just the single night together at the Warren County Fair, where, during the grandstand spectacular, the boom of aerial bombs had pounded the boy's eardrums, and he'd disappeared.

When the fire had faded and the concussions finally ceased, he'd reappeared pale and shaking from under the seats where fairgoers had watched the sulky races that afternoon.

Fae Anne had taken his hand as he wept about the Ardennes and Nebelwerfer rockets. And back in his father's car, with no idea what else to do, she'd offered her virginity in awkward and unpleasant sex.

But she'd never told him about the pregnancy and never named him as the father.

![]()

Eventually, penitent, Fae Anne turned back to the Evangelicals and Jesus and married another fellow with his own confidences, and unrealized opportunities of which the two never spoke.

The longer she spent with him and her church though, the more Fae Anne's belief in her personal sin had deepened. Her well of guilt and shame plunged bottomless, and worsened again after her second pregnancy and the child she would this time keep.

Too burdened with her past, she'd dreaded ever naming her son. She loved the boy she supposed, but wasn't he a sinner and a man, and wouldn't something dirty, some terrible desecration of his own making finally unfold over him?

And so into that child, she'd poured the bitters of her own shame where it blossomed dark and senseless and worse in him than in the original from where it had sprung.

Inevitably, without understanding why, the child fled mother and family to a place where no one would ever remark his being. And wary of all, particularly women, he'd refuse to speak his own name to anyone in this world or any other.

And thankfully, he was sure, even Jesus could never know his name or who he was.

|

13

favs |

1059 views

12 comments |

579 words

All rights reserved. |

Author's Note

From Wikipedia

The 21 cm Nebelwerfer 42 (21 cm NbW 42) was a German multiple rocket launcher used in the Second World War. It served with units of the Nebeltruppen, the German equivalent of the American Chemical Corps. Just as the Chemical Corps had responsibility for poison gas and smoke weapons that were used instead to deliver high-explosives during the war so did the Nebeltruppen. The name "Nebelwerfer" is best translated as "smoke-thrower". It saw service from 1942—45 in all theaters except Norway. It was adapted for aerial combat by the Luftwaffe in 1943.

Other stories by Steven Gowin

Tags

This story has no tags.

Powerfully written. Devastating. Yet, good to see you back, Steven!

Strong story, Steven.

"And so into that child, she'd poured the bitters of her own shame where it blossomed black and senseless and worse in him than the original from which it had sprung."

The closing is haunting. One of the inner needs that defines us is to leave a mark - make a change - find a niche. The child goes against this grain to a spot of not knowing / not being known-- "...he'd refuse to speak his own name to anyone in this world or any other." Great piece.

*.

"Yea, for I have seen the Father, the Son, and the Holy Toast."

Excellent work.

Excellent writing Mr. Gowin! Nicely done.

Wonderful writing. Moving.

You always mange to hit home, Steve.

"And so into that child, she'd poured the bitters of her own shame where it blossomed black and senseless and worse in him than the original from which it had sprung."

That sentence, in particular, haunts.

*

Excellent writing. *

I love writing that gets me all riled up. Here you have succeeded perfectly.

Evangelicals, indeed! *

"with no idea what else to do" *

I love it.

*****