Rwanda Suite: Buzzed

by Steven Gowin

The earth hummed on that coline, on that hill over the Fleuve Ruzizi and Lac Kivu, that beautiful dangerous water.

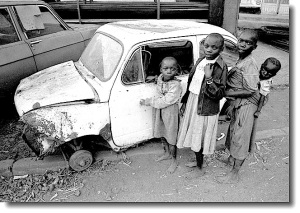

We'd hiked out from our stage, our training. The Belge had built this former boys' school when the Belge ran everything. Back then every mailman, every city clerk, every fonctionnaire was a white man from Antwerp or Ghent or Charleroi.

Pure greed, a pristine avarice, almost innocent. They'd taken so much: ivory, rubber, copper, gold. Wealth for the grabbing. No remorse. But 1 July, 1960, all changed. Abrupt, brutal, only diseased religion, abandoned schools, and Franco's Epic guitar left behind.

Duprée, my lazy eye friend, was a French American Jew. He'd marry a Congolese girl and manage rental cars in the Kasais. But that hot morning, as volunteers in training, we'd smoked reefer, we always did smoke reefer, and hiked Eastward, intending to find a cabaret, a cold Primus.

Our footpath climbed and fell, climbed and fell again and again. The sun beat violently, and although a deft breeze whispered across the ridges, it could not mitigate the heat and sécheresse. Finding no relief, no tavern, the tepid but sanitary water from Duprée's canteen refreshed us only poorly.

So we sat, sipping, in the heat, on the earth, on a ridge, to listen to Africa, to hear Africa and to rest. Congo to the West, Rwanda to the East, nothing existed but calm droning, a buzz, low, pleasing. Locusts. Wind in the grass, dust in the air. Africa sucked out all language.

Soon a man in brilliant white trousers and shirt approached us. My French was poor, and although Duprée spoke fine Parisian, he preferred a filthy patois from boarding school days in Switzerland. Before we'd spoken a word though, the traveler had pegged us as American.

Ibaka Nestor Marie worked as infimiere, as nurse, at Hôpital Saint Jean Bosco. He admired John Wayne; we surely knew him, non? And didn't all volunteers report to the CIA, and hadn't every Yank a fine friggo? Someday he would own a friggo too, a good cold one. We must follow him now. We were invité.

Holding my hand, he led us over the ridge, away from the frontier and the river and the lake down to a banana grove and small house with mud thatch walls and a tile roof extending over a shallow veranda. Furnishings were spare; the single room's only window opened to the hills. On the wall hung framed magazine photos of Bobby Kennedy, Martin King Jr., Mohammed Ali.

While Ibaka dragged a wooden table and stools to the porch and fussed with a tattered schmatta, a small boy rushed out to take a bunny from its garden hutch. Retuning to us, he proudly held it belly up puffing its soft fur to reveal the rabbit's sex. Then boy and rodent disappeared.

By now, our host had set the table with mustard glass, jelly jar, and a clean can for himself. He fetched a whiskey bottle three quarters full of something clear but heavy and greasy. Moonshine hooch. Warugu, Ibaka pronounced, eau de vie.

We drank and after a discussion of the best livestock and inquiries as to our cows and families, he called for his wife and children. A tiny scrubbed girl climbed onto his lap. The Rabbit Boy reappeared too, and Ibaka rested a hand on his head. The wife, in batik pagne and matching turban, hid behind her épouse.

We're several drinks in now. Duprée sets a capful afire, and it burns smokey and yellow. Strong and impure, it stings our mouths. Ibaka's Congo French becomes more difficult, but we gather that the children excel at study, and Papa dreams of great lives, médecins, ingénieurs.

But les études require books, uniforms, shoes, he explains. So did we not have a small present, a matabish, for les enfants? And like that he'd asked. No other prelude. Bald post colonial begging? I thought so then but do not now. Why? I can't explain.

What did Duprée and I have between us? Fifteen hundred, two thousand CDF, only a few dollars? We passed it over with blessing. Probably expecting wealthier mazungus, the pitiful gift surprised Ibaka, but he thanked us nevertheless and retuned the furniture inside.

As we stumbled up the footpath toward Bukavu, the entire family waved us goodbye. The afternoon still hummed and buzzed, the sun beat down worse than before, the dense air hung motionless. Our throats burned, our lips missed language.

Finally, back at stage in my Belgian child's bed, suffering nausea and a stabbing headache, I fell asleep wishing only for clean, iced, water.

|

12

favs |

1662 views

12 comments |

795 words

All rights reserved. |

Author's Note

Other stories by Steven Gowin

Tags

This story has no tags.

This writing is so finely wrought. I enjoy reading it immensely. *

This is some of your best. Really well done.*

A great capsule of the African experience, closely observed for the residue of the colonial relationship.

What Ann said, and then what Gary said, and, of course, what David said. Still trying to come up with something worthy of this rich tapestry myself to add to their kudos. *

I am so looking forward to the day when you collect and publish these pieces so I can have this work on my bookshelf. I would love it for the vocabulary alone. Great writing.

Strong piece, Steve. Agree with Carol. *

*, Steven. I'm really taken with the Rwanda Suite series and I also look forward to you collecting them into a novel/novella.

The ending is dynamite. *

Please tell me this is a book chapter. It is so brilliant in so many places. Or tell me it is the narrator's voice in a film and we will see it on PBS nationwide, The language has a richness that only a careful listener can then write.

"Africa sucked out all language....Our throats burned, our lips missed language." Oh Africa. What the colonials did to you. *****

Among my favorites in the series/suite/hoped for book.

Excellent writing, Steven.

*

Love these Rwanda stories, Steven. Each one relevant and well written.