My Fictional Tormenter

by Con Chapman

It was, I thought, an innocent act. My publisher called to say that the manuscript to my first book, The Year of the Gerbil, was finished, and that he had obtained a blurb, a quote in praise of the book for the back cover, and from a former director of public relations for the New York Yankees, no less. Had I, he asked, persuaded anyone to do likewise?

Having a single blurb is like having a single friend in grade school. Which I usually did, until they moved away, in which case I got my next one. It's worse than keeping to yourself; when you do that, you could be a brooding genius, or an angry loner. Walk around with the same kid every day at recess and when he gets the mumps everyone recognizes you for what you are; a leech, a lamprey, a bloodsucker, one who needs companionship but lacks the capacity for friendship needed to develop and maintain two friends at one time.

So I lied. “Yes,” I said, “I've got a quote from a professor—quite a glowing one, too.”

“Oh, really,” the publisher said. “What's the guy's name?”

“Have you got a pencil?” I asked.

“Shoot.”

“E-t-a-o-i-n . . . “

“e . . t . . a . . o . . i . . n?” he repeated.

“Right. Last name, s-h-r-d-l-u.”

“s . . h . . r . . d . . l . . u?”

“That's it.”

“How do you pronounce it?”

“EE-shun SHRED-lu.”

“What is that, Chinese?”

“Sino-Turkish,” I said. “He's Professor of Comparative American Literature at the University of Missouri-Chillicothe.”

“Never heard of it,” he said. The guy was a real East coast provincial, ensconced down in some quaint little town in Connecticut, wholly ignorant of the world beyond the Hudson. I couldn't believe he'd never heard of the fictional land grant college I'd just made up. “So what's the quote?” he asked.

“A mere little book about baseball, in the sense that Moby Dick is a merely a book about fishing.”

There was a pregnant pause at the end of the line. “Wow—that's great,” the guy said. “I'm going to highlight that in bold at the top.”

I felt a sense of liar's remorse. It's one thing to lie to your parents, your wife, your kids, your boss, the shareholders of a publicly-traded corporation or the congregation of non-mainline Protestant church, as so many televangelists do. It's something else entirely to lie to a man who's persuaded himself that you've written what will become the best-selling book in his pathetic little company's history, ordering a double run of not one, but two thousand copies.

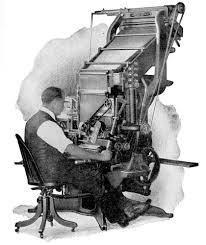

Linotype machine

And yet, I thought to myself, what I'd just done wasn't so bad. Mark Twain had, after all, written reviews of his own books under a different name. And I had laid the key to my deception out in plain view for the guy, and the world, to decipher, in the manner of C. Auguste Dupin, the Parisian amateur detective in Poe's The Purloined Letter. “etaoin shrdlu” is a combination of two sequences of letters on a hot-lead linotype machine, as every schoolboy who has ever taken a course in typesetting before the advent of computers surely knows. When the machine jams, the entire slug drops so that these letters appear accidentally in the printed text. It was, as Flannery O'Connor once wrote, as plain as a pig on a sofa.

Flannery O'Connor

But my publisher was a benighted occupant of that quotidian realm where these things have been forgotten; all he and anyone else cares about these days is relevant facts, not the useless trivia I had accumulated over a lifetime of woolgathering.

And so the book appeared in print, and the person of Etaoin Shrdlu was loosed upon the world. He subsequently surfaced in a ficcione, a tale of his bootless pursuit of a reclusive poetess, modeled on one I'd met on-line. I wrote that Shrdlu was a specialist in the Midwestern Smart-Aleck School of Literature, and that he was known for his writings on Ring Lardner and George Ade, neglected masters of the genre. A state legislator in Missouri, Claude Boulrice (D-Knob Noster), read a wire-service report in which Shrdlu was mentioned, and rose on the floor of the General Assembly in the State Capitol in Jefferson City to denounce Shrdlu's works as “frivolous, a waste of money, and a corruption of the morals of our young men and women at taxpayer's expense.” I had, by my mischief, exposed a fictional character to slander; I could only laugh.

Ring Lardner

But Shrdlu, however, could not. He had been called upon to do more than one should expect of an imaginary man. First, he had been brought into being—fair enough. Second, he had been compelled to compare me to Herman Melville, a laughable simile, and one for which he had been justly criticized by other characters both high and low; Sutpens from Faulkner's Absalom, Absalom!, Fred C. Dobbs, an American prospector in B. Traven's The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. Finally, Shrdlu had been forced to endure the obloquy of the unlettered, the scorn of the Puritanical solon, a typical example of H.L. Mencken's booboisie for whom an open book was never an open book. He would have his revenge.

Humphrey Bogart as Fred C. Dobbs

And so I began to notice, when I would search for reviews of my writing, that I was mentioned as the author of works I had never heard of. “Thirty Days to a Less Powerful Vocabulary” was included on my amazon.com author's page. “Figures of Dionysus in Topps Baseball Cards” was mentioned as the work that had first brought my theories to the attention of classical scholars. “I Can Smell You From Here,” a memoir of my grade school years. None ever existed, or ever will.

Then there were the footnotes. As Shrdlu's oeuvre grew, his research was cited by others; a specialist on Kim Jong-il's collection of DVDs; the author of a monograph on the NFL Cardinals' dismal tenure in St. Louis; a history of “soul” dances—boogaloo, shingaling, hucklebuck—of the 1960s. Shrdlu's response was excessive, but to whom could I complain?

Sonny Randle of St. Louis (football) Cardinals, inside Coke cap

Finally, he administered the coup de grace; an obituary that described me as a former head of the Catholic Legion of Decency, responsible for the “Condemned” rating assigned to Hotfoot: The Bud Zaremba Story, a biopic of a practical joking knuckleball pitcher. My career was over if I couldn't get the Worcester News-Recorder to print a retraction. I met Shrdlu at George's Coney Island Hotdogs in that doleful central Massachusetts city, the Industrial Abrasives Capital of the World.

“You know what I'm here for,” I said to him as we sat down in one of the booths.

“A chili dog and a chocolate milk?” he said with a sneer.

George's Coney Island Hot Dogs, Worcester, Mass.

“Real funny. I want my reputation back.”

“What is it Little Milton says? ‘Welcome to the club'?”

He had me there. “Look—what's it worth to you?”

“I never wanted to be part of your grimy little world, filled with snide remarks and characters whose names you think are so funny.”

“So what am I supposed to do now? The book's out there.”

“First, you can take down this stupid post."

"The one we're in right now."

"The same—tonight. That won't be so hard.”

He was right about that. It was up on a couple sites, but in a few weeks the cached pages would disappear from the internet. “Consider it done,” I said with resignation. “What else?”

“The books.”

“What about ‘em?”

“Take ‘em to the dump.”

I figured he was bluffing. “C'mon—the publisher's out of business.”

“You should have let him pulp those puppies when he offered to.”

“I've only got like . . . eight boxes of 28 left.”

“That's 1,775 copies floating around out there, putting words in my mouth that I never said. Haven't you done enough damage to my reputation?”

“What reputation? You didn't even exist before I put you on the cover.”

“So? I'm fictional. I didn't have to come into the world with your original sin.”

In purely theological terms, he had a point. He was a product of my imagination, not a just and merciful God. Nobody ever chased a character in a novel out of the Garden of Eden.

“All right,” I said finally. “It'll take me a couple of weekends, but I'll do it.”

He seemed satisfied. “I'm glad we could come to terms.”

“And you'll leave me alone now?”

“From this moment on, you're only liable for what you do, not what I say you do. And I'd be much obliged if you'd extend the same . . . professional courtesy to me.”

Why, I thought finally, should I care? Characters came cheap in my brain. They were as plentiful as dandelions and they had about the same life span, popping up only to get lopped off by the weed-wackers wielded by my two hands' worth of literary lawn guys, who'd delete them at their whim whenever a new and more bizarre news clipping came along: Giant Jellyfish Attacks 100 Off New Hampshire Coast. Bear Hijacks Car in Yellowstone. And my favorite: Dog Nearly Itches to Death.

“Okay—you have my word.”

“That's good enough for me,” he said. “After all—I am your words.”

|

2

favs |

1937 views

5 comments |

1763 words

All rights reserved. |

Author's Note

The author has not attached a note to this story.

Other stories by Con Chapman

Tags

This story has no tags.

The Year of the Gerbil??????

Why not? The Chinese have a Year of the Rat.

It's a book about the '78 AL East pennant race. The manager of the Red Sox was nicknamed "The Gerbil" by one of his younger players and it stuck.

Love it! The Sino-Turkish blurber. and "characters came cheap to my brain." Nice mix of cynicism and humor in this piece, Con.

Whenever I'm in New York, I like to eat Sino-Turkish. You can't get that where I live.

"I couldn't believe he'd never heard of the fictional land grant college I'd just made up."

You're great, Con! Another wonderful piece.

Ever read Niebla by Unamuno? At Swim-Two Birds by Flann O'Brien? You join their august company.