Girls U-10 Soccer Yakuza

by Con Chapman

NEEDHAM FALLS, Mass. In this leafy suburb of Boston fall weekends are dominated by youth soccer, and Department of Public Works employee Paul Quichette is dreading it. “You'd think some of these families lived in a pig sty,” he says as he pokes at a discarded orange rind using a stick with a nail embedded in one end. “I didn't go to community college for two semesters to learn how to do this.”

Post-game mess in the making.

The overtime the town must pay and the damage to lawn mowers from plastic bottles in the spring forced a decision by the Board of Selectmen to resort to tougher measures than signs posted around soccer fields this season. “I'd heard great things about the response of the Yamaguchi-guma,” Japan's largest yakuza family, “to the Kobe earthquake in Japan,” says Town Manager Ellen Benoit-Walker. “After a Sunday of twelve back-to-back games, we certainly have a disaster on our hands.”

“You gonna pick up that Evian bottle, or am I gonna have to get rough?”

Yakuza are members of traditional organized crime syndicates in Japan. While police characterize them as boryokudan, a term that means “violence group,” the yakuza consider themselves ninkyo dantai, or “chivalrous organizations.”

“Mommy, that man's scaring me!”

Like the Mafia, yakuza are organized along heirarchical lines that replicate familial and political structures. While they derive their revenue from illicit activities such as gambling and prostitution, they have a penchant for order that makes them an outlaw alternative when civil society breaks down, in much the same manner that La Cosa Nostra keeps crime—by people other than themselves—at a minimum in Italian urban neighborhoods on the East coast.

“No hanging back by the goal in 3-on-3 Kinderkick!”

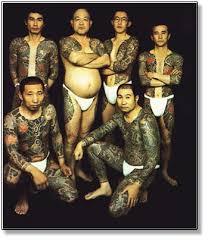

A squad of two gokudo patrols the perimeter of Centennial Field, watching the girls U-10 action on twelve reduced-size soccer pitches surrounded by orange cones. Their irezumi—gaudy tattoos—draw stares from suburban parents who are used to seeing such grotesque physical embellishments only on boyfriends their elder daughters bring home from liberal arts colleges.

“What happened to your pinky?”

“Hey,” barks Hisayuchi Machii at a girl with blonde pigtails. “Pick up your Evian bottle!”

The girl jumps, unused to such a harsh tone of reproof since her mother uses a cleaning crew composed of illegal aliens to pick up around the house.

“And put it in the trash container—over there,” seconds Jiro Kiyota.

“Go Needham—beat Wellesley!”

The girl complies, and the men nod their approval. “This is correct, young kobun,” a term that means “foster child” and refers to one who has pledged allegiance to an oyabun, or foster parent within a yakuza family. Seventy percent of yakuza are descendants of Burakumin, outcasts of Japan's feudal era who were consigned to tasks considered tainted with impurity, and so trash collection is hard-wired into their genetic makeup.

“Your tattoos are awesome!”

There is a shout on the field as Emily Neidermeyer, the star of the Fred's Hardware Comets, scores a goal, but the momentary burst of euphoria is chilled when a father from the opposite sideline approaches Nancy Thibeault, the team's coach, and makes clear his displeasure with what he regards as illegal play.

“You can't hang back in three-on-three Kinderkick because there's no goalie,” he says, growing red in the face. “I'm gonna report you to the league.”

The two men have only been working the sidelines for a month, but yakuza form strong bonds of attachment based on jingi, their code of loyalty and respect as a way of life. They exchange glances, then spring into action.

“Excuse me, Wellesley-san,” Kiyota says. “I believe the Code of Sportsmanship of the Metrowest Girls Soccer League requires you to direct your anger towards the referee, not your opponents' coach.

“It is Rule 4.06,” adds Machii, with a menacing tone. “That's at Tab 4 of the white, three-ring binder provided to all coaches at the beginning of the season.”

The Wellesley coach, who was red-faced just a moment before, turns ash-grey when he sees the traditional Japanese swords borne by the yakuza.

“Can I have my pinky back after the game?”

“You're . . . uh . . . right,” says the man. “My bad.”

“That was not much of an apology,” says Kiyota. “You must do more.”

“Like what?” the man says. “Get down on my knees?”

“No, nothing like that,” says Machii. “Hold out your left hand.”

The man's face breaks out in an antic expression, as if he is going to have his hand smacked with a ruler. “Okay,” he says with a goofy grin. “Now what?”

“This,” says Kiyota, as he swings his sword down on the man's pinky, cutting off the tip in the penance ritual of yubitsume, Japanese for “finger shortening,” also known as yubi o tobasu or “flying finger.”

It's in there somewhere.

“Jesus Christ!” the man screams in pain, and a chorus of “Ewww” is heard from the Needham bench, where the severed body part has landed in a Yoplait strawberry yogurt.

Machii approaches the girls and removes the finger tip from the container, then presents it to Coach Thibeault. “Here is your iki yubi” or “living finger,” he says. “This asshole now accepts you as his kumicho.”

“What does that mean?” the owner of the suddenly-shorter finger asks.

“It may be girls soccer,” Kiyota says, “but she is now your godfather.”

Available in Kindle format on amazon.com as part of the collection “Boston Baroques.”

|

0

favs |

1535 views

0 comments |

1041 words

All rights reserved. |

Author's Note

The author has not attached a note to this story.

Other stories by Con Chapman

Tags

This story has no tags.