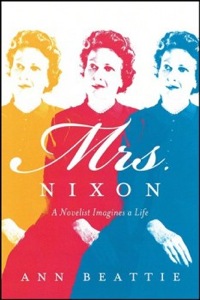

Though Thelma Ryan later married Richard Nixon and went through a life of nick names both with and before she met him—they were married more than 50 years—dubbing herself Patricia while yet in college—“Buddy,” “Miss Vagabond,” “Irish Gypsy,” “St. Patrick’s Babe in the Morn,” “Babe,” “Pat,” “Miss Pat,” “Patricia,” “Dearest Heart,” “The White Sister,” and “Starlight”—it seems inevitable that the not-novel, not-biography, not-memoir written by Ann Beattie and bearing the former first lady’s name would be called Mrs. Nixon, befitting both the era she occupied and her formal distance yet iconic status in the public’s mind.

Though Thelma Ryan later married Richard Nixon and went through a life of nick names both with and before she met him—they were married more than 50 years—dubbing herself Patricia while yet in college—“Buddy,” “Miss Vagabond,” “Irish Gypsy,” “St. Patrick’s Babe in the Morn,” “Babe,” “Pat,” “Miss Pat,” “Patricia,” “Dearest Heart,” “The White Sister,” and “Starlight”—it seems inevitable that the not-novel, not-biography, not-memoir written by Ann Beattie and bearing the former first lady’s name would be called Mrs. Nixon, befitting both the era she occupied and her formal distance yet iconic status in the public’s mind.

As soon as I understood that Ann Beattie had written a book called Mrs. Nixon, I did not believe, as some readers may have, that she had written a novel about Pat Nixon. I knew it was about Pat Nixon, wife of Richard Nixon, but I thought it was more likely a biography, and I asked, instantly, why has the famous minimalist short story writer turned to writing biography? Then I recalled that I had read that Lydia Davis, too, has shown an interest in it, and Virginia Woolf had famously praised the art of biography in her criticism. I could not quite have imagined that the book Beattie turned out is not a biography or novel or memoir or how-to write manual, but a pastiche of all these, set forth in what might be an unprecedented blend of prose genres and elements. It was written, and not only written but produced, against certain odds and with a certain bravery. It defies not only the expectations of Beattie’s own readers, readers’ readers who follow her through all her guises and stylistic innovations, from story to story, hooked on the next manifestation of her thinking in fiction; it was also written in defiance of expectations of fiction itself, of biography itself, and of how-to write manuals. It could be a blue print for how to write a how-to write manual, one that demonstrates the discipline of sticking with facts and filling in their gaps with plausible, from a realist angle, conjectures about life lived between known lines. The duty to stay with reality is stronger in writing about a public figure, one who will forever be in the pantheon of history, than it is in writing about a private citizen or even famous actor, artist, or musician, whose inclusion in history seems predicated on taste over time. Beattie sidesteps the danger of replacing fact with fiction.

Reviews of Ann Beattie’s book seem divided—Beattie has this time both wittily perplexed and offended reviewers at The New York Times. By contrast, throughout the blogosphere, Beattie’s conceit, writing about Pat Nixon “as a paper doll,” as Michiko Kakutani describes it unsympathetically, garners significant appreciation as fictional experiment. It comes as a surprise to most of her readers that Beattie departs so completely from her usual style in writing fiction, but as I reflect, it does not surprise me. Years ago, at least ten, researching on the Internet for a possible anthology of essays by writers of experimental fiction, I came across Ann Beattie’s name more than twice and more than that of any other fiction writer of similar standing. It seems her interest in the experimental came before her implementation of it in Mrs. Nixon.

In her preface to her essay, “A Thought is the Bride to What Thinking,” Lynn Hejinian writes, “Prose is not a genre but a multitude of genres. […]Intrinsic to the existence of boundless multitudes is the impossibility of comprehensiveness and therefore of comprehension.” I feel that Beattie combines prose genres in Mrs. Nixon in ways that give forth to the infinite possibilities of prose itself. Juxtaposition is one way; listing another; speculative nonfiction and fiction two others (speculative may refer here to guessing about a real life, facts that cannot be known but that can be surmised with the educated eye of a novelist). Beattie also accesses literature: exegeses of Raymond Carver, Anton Chekhov, Tennessee Williams, Guy de Maupassant, and others lend to her pursuit of the quiet and unassuming, hardworking farm girl who grew up to become first lady.

What is perhaps most surprising about the book is that the joke of its title—a joke not told at Pat Nixon’s expense but about her rise to prim dominance in American culture—is sustained as a book-length carapace rather than as a one-liner or humorous title never written. It is an experiment laid out for study and recreation.

Ann Bogle has been a member at Fictionaut since July 2009. She is fiction reader at Drunken Boat, creative nonfiction and book reviews editor at Mad Hatters’ Review, and served formerly as fiction editor at Women Writers: a Zine. She earned her M.F.A. in fiction at the University of Houston in 1994. Her stories have appeared in journals including Blip, Wigleaf, Metazen, Istanbul Literary Review, The Quarterly, Gulf Coast, Fiction International, Big Bridge, Thrice Fiction, fwriction : review, THIS Literary Magazine, and others. Her short collections of stories, Solzhenitsyn Jukebox and Country Without a Name, were published by Argotist Ebooks in 2010 and 2011. Books at Fictionaut features reviews of books published by Fictionaut contributors. A shorter version of this review appeared in the Fiction Reviews section of the print-only version of Rain Taxi, Vol. 17, No. 1, Spring 2012.

No Comments

Leave a Comment

trackback address