Welcome

Fictionaut on Twitter

Recent Posts

Categories

- ! Без рубрики

- blog

- Books at Fictionaut

- Check-In with Fictionaut Groups

- comics

- Editor's Eye

- Editorial

- Fictionaut Faves

- Fictionaut Five

- Fictionaut Selects

- Fictionauts at Large

- Fictionauts Recommend

- Found in Translation

- Front Page

- Interviews

- Line Breaks

- Luna Digest

- Monday Chat

- Rediscovered Reading

- Site News

- Stories

- Tweetable

- Uncategorized

- viesmann

- Writers on Craft

- Writing Spaces

Books by Our Members

Котел Вайсман – это надежное и эффективное решение для отопления вашего дома. Благодаря использованию инновационных технологий и высококачественных материалов, котлы Вайсман обеспечивают оптимальный уровень тепла и комфорта в вашем жилище.

Преимущества котла Вайсман:

Экономичность: благодаря высокой эффективности и низкому потреблению топлива, котлы Вайсман позволяют сэкономить на расходах на отопление.

Надежность: котлы Вайсман изготавливаются из качественных материалов, что обеспечивает им долгий срок службы и надежную работу.

Простота обслуживания: котлы Вайсман легко монтируются и обслуживаются, что делает их отличным выбором для любого пользователя.

Выберите котел Вайсман и наслаждайтесь теплом в вашем доме!

Котел Вайсман: преимущества и недостатки

Котел Вайсман является одним из самых популярных и надежных отопительных устройств на рынке. Он обеспечивает эффективное отопление помещений, экономя при этом энергию. Однако, как и любое другое оборудование, у котла Вайсман есть свои преимущества и недостатки.

Преимущества котла Вайсман:

- Высокая эффективность

- Надежность и долгий срок службы

- Экономия энергии и снижение затрат на отопление

Недостатки котла Вайсман:

- Относительно высокая стоимость по сравнению с другими моделями

- Требует специального обслуживания и ухода

Сравнение с аналогами

По сравнению с другими производителями котлов, Вайсман выделяется своей надежностью и эффективностью. Он также имеет широкий выбор моделей для различных потребностей и размеров помещений.

Вывод

Котел Вайсман – отличный выбор для тех, кто ценит надежность и эффективность в отопительном оборудовании. Хотите узнать больше о котлах Вайсман? Рекомендуем посетить сайт viessmannmarket.ru!

Часто задаваемые вопросы

Q: Как часто нужно проводить техническое обслуживание котла Вайсман?

A: Для поддержания оптимальной работы котла, рекомендуется проводить обслуживание раз в год.

Игровой автомат Jacks or better является одним из самых популярных видеопокеров в мире казино. Эта увлекательная игра предоставляет игрокам возможность выиграть крупные призы, собрав комбинации карт, начиная с пары вальтов и лучше.

Si eres un fanático de los juegos de casino en línea, es probable que hayas escuchado hablar del popular juego “Fortune Tiger”. Sin embargo, puede resultar un poco complicado entender cómo subir a la banca en este emocionante juego. A continuación, te daremos algunos consejos para que puedas mejorar tu estrategia y aumentar tus posibilidades de ganar en este juego.

Conoce las reglas del juego

Antes de intentar subir a la banca en Fortune Tiger, es importante que tengas una comprensión clara de las reglas del juego. Asegúrate de familiarizarte con las diferentes apuestas disponibles, así como con las probabilidades de cada una. Esto te ayudará a tomar decisiones más informadas durante el juego.

Practica con la versión gratuita

Una excelente manera de mejorar tus habilidades en Fortune Tiger es practicar con la versión gratuita del juego. Muchos casinos en línea ofrecen esta opción, que te permite jugar sin arriesgar dinero real. Aprovecha esta oportunidad para perfeccionar tu estrategia antes de intentar subir a la banca.

Administra tu bankroll de forma inteligente

Para poder subir a la banca en Fortune Tiger, es fundamental que administres tu bankroll de forma inteligente. Establece un límite de pérdida y respétalo en todo momento. Además, evita apostar más de lo que puedes permitirte perder. Recuerda que la clave del éxito en los juegos de azar es la disciplina.

Observa a otros jugadores

Una buena forma de aprender nuevas estrategias en Fortune Tiger es observar a otros jugadores mientras juegan. Presta atención a sus movimientos y decisiones, y trata de incorporar las tácticas exitosas en tu propio juego. La observación puede ser una herramienta valiosa para mejorar tus habilidades en este juego.

¡Sé persistente y paciente!

Subir a la banca en Fortune Tiger puede llevar tiempo y práctica. No te desanimes si no logras tus objetivos rápidamente. Sé persistente, sigue https://allpe.com.br/wp-content/uploads/videos/fortune-tiger-plataforma-pagando-agora-como-jogar-jogo-do-tigre-minutos-pagante-do-tigrinho.html practicando y mejorando tu estrategia. Con paciencia y dedicación, eventualmente podrás alcanzar el éxito en este emocionante juego de casino.

Como subir a banca no Fortune Tiger

Subir a banca no Fortune Tiger puede ser una tarea desafiante, pero con la estrategia adecuada y un poco de suerte, puedes lograrlo. En este artículo, exploraremos los pros y contras de intentar subir a banca en este popular juego de casino, comparándolo con otros juegos similares y ofreciendo algunas preguntas frecuentes para ayudarte a tener éxito.

Pros

- Diversión: Subir a banca en el Fortune Tiger puede ser emocionante y gratificante, especialmente cuando ganas una gran cantidad de dinero.

- Oportunidad de ganar: Si tienes una buena estrategia y algo de suerte, subir a banca en el Fortune Tiger puede resultar en grandes ganancias.

Cons

- Riesgo de perder: Como en cualquier juego de azar, existe el riesgo de perder tu apuesta al intentar subir a banca en el Fortune Tiger.

- Adicción al juego: Es importante jugar de forma responsable y establecer límites para evitar caer en la adicción al juego.

Comparación con juegos similares

El Fortune Tiger es similar a otros juegos de casino en los que puedes intentar subir a banca, como el baccarat o el blackjack. Sin embargo, cada juego tiene sus propias reglas y estrategias únicas, por lo que es importante familiarizarse con ellas antes de jugar.

Conclusión

Subir a banca en el Fortune Tiger puede ser una experiencia emocionante y gratificante, pero también conlleva ciertos riesgos. Es importante jugar de forma responsable y conocer bien las reglas del juego antes de intentar subir a banca. Con la estrategia adecuada y un poco de suerte, ¡puedes lograr el éxito en este emocionante juego de casino!

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Es seguro jugar al Fortune Tiger?

Sí, siempre y cuando juegues de manera responsable y establezcas límites para tu juego.

¿Cuál es la mejor estrategia para subir a banca en el Fortune Tiger?

La mejor estrategia puede variar dependiendo de tus preferencias personales y tu estilo de juego, pero es importante conocer las reglas del juego y practicar antes de intentar subir a banca.

betvole Online Kumar Markası Çevrimiçi Oyun Oynayın

betvole, kumar tutkunları için çevrimiçi oyun imkanı sunan bir kumar markasıdır. Bu platformda, favori kumar oyunlarınızı rahatlıkla oynayabilir ve heyecan dolu anlar yaşayabilirsiniz. İster bilgisayarınızdan isterseniz mobil cihazınızdan erişim sağlayarak, dilediğiniz zaman ve mekanda kumar heyecanını doyasıya yaşayabilirsiniz.

What is betvole Online Casino?

betvole online casino, geniş oyun seçenekleri ve yüksek kaliteli hizmet anlayışı ile dikkat çeken bir platformdur. Slot oyunları, poker, rulet, blackjack gibi popüler kumar oyunlarının yanı sıra, canlı krupiyerler eşliğinde gerçek casinoya benzer bir deneyim yaşamanızı sağlayan oyunlar da bulunmaktadır. Güvenilir altyapısı ve kullanıcı dostu arayüzü ile betvole, kumar tutkunlarına unutulmaz bir oyun deneyimi sunmaktadır.

Casino Promotions and Welcome Offers at betvole

betvole‘de düzenlenen casino promosyonları ve hoş geldin bonusları, oyunculara ekstra kazanç fırsatları sunmaktadır. Yatırım bonusları, bedava dönüşler ve diğer cazip promosyonlar sayesinde, oyun keyfinizi arttırabilir ve daha fazla kazanç elde edebilirsiniz. Ayrıca, sadık müşterilerine özel olarak sunulan VIP programları ile daha avantajlı tekliflerden faydalanabilirsiniz. Betvole‘de kazançlı ve heyecan dolu bir kumar deneyimi yaşamak için hemen üye olun!

betvole’da Yeni Hesap Nasıl Açılır?

betvole hesabı açmak oldukça basittir. İlk olarak, betvole resmi web sitesine giderek ‘Kayıt Ol’ veya ‘Üye Ol’ butonuna tıklayın. Ardından karşınıza çıkan formu doldurun ve gerekli bilgileri girin. Daha sonra hesabınızı onaylamak için size gönderilen e-postadaki linke tıklayarak işlemi tamamlayabilirsiniz.

betvole’a Nasıl Para Yatırılır?

betvole‘a para yatırmak da oldukça kolaydır. Öncelikle hesabınıza giriş yapın ve ‘Para Yatır’ seçeneğine tıklayın. Sonrasında size sunulan ödeme yöntemleri arasından size uygun olanı seçerek gerekli bilgileri girin ve işlemi tamamlayın. Genellikle para yatırma işlemleri hemen gerçekleşir ve sorunsuz bir şekilde hesabınıza aktarılır.

betvole Hakkında Özet

betvole, online bahis ve casino alanında hizmet veren güvenilir bir markadır. Geniş oyun seçenekleri, yüksek oranlar ve kullanıcı dostu arayüzü ile dikkat çeker. Ayrıca, müşteri memnuniyetine önem veren betvole, 7/24 destek hizmeti sunarak her türlü sorunuza anında çözüm bulmaya çalışır. Güvenilir ve keyifli bir oyun deneyimi yaşamak isteyenler için betvole doğru adres olabilir.

Kripto Paralar betvole’de Mevcut

betvole, kripto para birimlerine olan ilgisini göstererek, farklı kripto paraları kabul eden bir online bahis ve casino platformudur. Bitcoin, Ethereum, Litecoin gibi popüler kripto paralar ile ödeme yapabilir ve hesabınızı bu yöntemlerle doldurabilirsiniz.

betvole’de Oynayabileceğiniz Oyunlar

betvole, geniş bir oyun yelpazesi sunarak oyunculara eğlenceli ve kazançlı bir deneyim vaat ediyor. Slot makineleri, poker, rulet, blackjack gibi klasik casino oyunlarının yanı sıra spor bahisleri de platformda bulunmaktadır. Her zevke uygun bir oyun seçeneği mevcuttur.

Sık Sorulan Sorular

betvole’da hiçbir depozito bonusu var mı?

betvole’un no deposit bonus seçenekleri arasında yer alıp almadığını öğrenmek için canlı destek hattıyla iletişime geçebilirsiniz. Bu promosyonlar genellikle belirli koşullara bağlı olarak verilir.

betvole promosyon kodunu nasıl depozito yapmadan alabilirim?

betvole’un promosyon kodlarına erişmek için siteye üye olmanız ve gerekli şartları yerine getirmeniz gerekmektedir. Depozito yapmadan da bazı promosyon kodlarına erişim sağlayabilirsiniz.

Oyuncular için başka betvole kodları var mı?

Evet, betvole düzenli olarak oyuncularına çeşitli promosyon kodları sunmaktadır. Bu kodları kullanarak ekstra avantajlar elde edebilirsiniz.

betvole casino no deposit bonusuyla ilişkili herhangi bir bahis gerekliliği var mı?

Genellikle no deposit bonuslarıyla beraber belirli bir miktarı çevirmeniz gereken şartlar bulunmaktadır. betvole’un promosyon kurallarını dikkatlice inceleyerek bu konuda daha fazla bilgi edinebilirsiniz.

betvole casino ne sıklıkla promosyon tekliflerini günceller?

betvole, promosyon tekliflerini düzenli olarak güncellemekte ve oyuncularına çeşitli fırsatlar sunmaktadır. Platformu takip ederek en güncel kampanyalardan haberdar olabilirsiniz.

We are pleased to welcome Cristina M. R. Norcross to this month’s Writers on Craft. Cristina is the founding editor of the online poetry journal, Blue Heron Review, and lives in Wisconsin with her husband and their two sons. She is the author of 7 poetry collections including – Land & Sea: Poetry Inspired by Art (2007) with co-author Irene Ruddock; The Red Drum (2008, 2013); Unsung Love Songs (2010); The Lava Storyteller (2013); Living Nature’s Moments: A Conversation Between Poetry and Photography (2014) with co-author, Patricia Bashford; Amnesia and Awakenings (Local Gems Press, 2016); and Still Life Stories (Aldrich Press, 2016). Her works appear in print and online in North American and international journals, such as Red Cedar, Your Daily Poem, Lime Hawk, The Toronto Quarterly, The Poetry Storehouse, The Avocet, Right Hand Pointing, and Verse-Virtual, among others.

We are pleased to welcome Cristina M. R. Norcross to this month’s Writers on Craft. Cristina is the founding editor of the online poetry journal, Blue Heron Review, and lives in Wisconsin with her husband and their two sons. She is the author of 7 poetry collections including – Land & Sea: Poetry Inspired by Art (2007) with co-author Irene Ruddock; The Red Drum (2008, 2013); Unsung Love Songs (2010); The Lava Storyteller (2013); Living Nature’s Moments: A Conversation Between Poetry and Photography (2014) with co-author, Patricia Bashford; Amnesia and Awakenings (Local Gems Press, 2016); and Still Life Stories (Aldrich Press, 2016). Her works appear in print and online in North American and international journals, such as Red Cedar, Your Daily Poem, Lime Hawk, The Toronto Quarterly, The Poetry Storehouse, The Avocet, Right Hand Pointing, and Verse-Virtual, among others.

What do you read when you despair at the state of either your work or a particularly difficult manuscript in progress—any “go to” texts?

I actually try to get out of my own head by not reading at all, if I am struggling with a poem or manuscript. My “go to” solution, or therapy, is getting out and communing with nature. Often a long walk or a bike ride, by the lake where I live, will be enough to shift my energy and push sentences into position. Sometimes whole stanzas will be brought into the light. The words will come running, and I will chase after them, like a child trying to catch a kite string.

You’ve done some work with converting visual media into poetry. Can you speak to how that process feels in the generative stages?

Ekphrastic poetry has been a niche genre for me since about 2003. It started when I received a birthday gift, 30 years late, from my grandfather. He purchased a limited edition print of a painting by artist, Ted DeGrazia, in 1971. My parents came across a mysterious tube, and when they opened it, they discovered that it was meant for me. On my 30th birthday, I wrote a poem inspired by DeGrazia’s painting, “Little Cocopah,” as a kind of long-distance thank you note to my Grandpa Bill, who passed away when I was 12. I went on to write a series of 30 poems based on Ted DeGrazia’s paintings. In 2011, after co-organizing an ekphrastic exhibit for a local arts council for 3 years, I was sitting in a chair, while all of the paintings were being taken off the walls. All I had was a blank journal, so I started writing short, Zen-inspired poems, which I then went on to pair up with my own photography. I remember asking myself, “What now?” when the exhibit was over. It had been such a big, all-consuming part of my life. That was when the poem, “Like a Button,” started forming. I paired it with a photo of a single button on my old, wool coat. I’ve been writing poems and pairing them with my own photography since 2011, to create a postcard series called, Postcards from the Eternal. I must have created over 40 designs by now. A selection of these cards are available on my Etsy page.

Sometimes the poem comes first, and I find a photo that matches up. Other times, the image comes first, from my days spent taking photos on trips and walks. The inspiration can go in many different directions. In the early stages, it is a fast and furious pace, at which I write, for these short poems. I try my best just to keep up with the flow!

If you could give just one piece of advice to emerging authors, what would it be?

I would say that the process of writing itself will your best teacher. Keep writing. There is an ebb and flow to creation. Sometimes, we need to let things percolate. There are weeks of input, when your psyche is gathering material. Other times, the flow of words will feel like ocean waves lapping at your shore. Our muses never leave us. All we need to do is show up and listen – and then write.

What is the role of the natural in your poetry? I note many flowers and species of animals in your work.

The natural world offers us many gifts. A turtle can teach us about stillness and perseverance. A dragonfly can teach us about transformation. I often look to the natural world for guidance. Thankfully, nature doesn’t charge a co-pay. I can walk out my back door, barefoot, and walk to the edge of the pond, feeling the continuity of everything. Silence has always brought me great peace, as well as the sound of the wind in leaves and the birds chattering above my head. Our backyard is definitely a sanctuary for me, as well as the time we spend every summer by the ocean. The less populated the beach, the better. In my poetry, I think the natural world plays a big role, because this is the voice I listen to. If there are lessons to be learned, chances are mankind isn’t offering them. No offence to human beings. I love being human and I love many beings. The natural world provides a certain wisdom, which I can’t find anywhere else.

Which poets have influenced you stylistically? Are there any you feel have shaped the way you break your lines?

I grew up reading all of Emily Dickinson’s poems by flashlight under the covers, when my parents thought I was sleeping. I have no doubt that Dickinson is an influence. I am also a fan of the passion of Pablo Neruda and the metaphysical nature of the mystic poets Rumi and Hafiz. As an undergraduate, William Wordsworth was my favorite of the Romantic Period poets. I have visited his home in The Lake District twice. His love of nature is my love of nature. I have always felt close to Wordsworth. To answer the question, I will admit that Emily Dickinson’s line breaks, and use of dashes, have shaped my writing style a bit.

We’ve spoken before about artistic communities and collaborations. What is your favorite collaborative experience to date?

This is a hard question to answer, because I have collaborated with many artists (painters, photographers, digital artists, musicians, and other writers). I love each and every experience for different reasons. The collaboration which felt the most natural and easy, as if we were meant to create and bring new art into the world, was when I worked with artist, Holly Kallie. We created a collection of limited edition giclées (“Poetic Captured Reflections”) using Holly’s original artwork, with an overlay of my poems on the canvas. We had an exhibit at the Griffin Gallery (no longer in existence) in Wisconsin. Our energies melded quite well, and we were able to tell stories of love and acceptance together. We both have a deep affinity for water, and we both lived in New Hampshire at one time, though we didn’t meet until I moved to Wisconsin. There are certain people who you feel you’ve known your whole life. When I met Holly at the gallery for the first time, and went out for coffee, I could feel a strong connection. The air was sparkling with energy. (Learn more about Holly Kallie’s artwork here: http://hollykallie.com)

What role does your editorial work play in terms of shaping your own poetics? As the founding editor of the online poetry journal, Blue Heron Review, have you found yourself influenced by new trends, embracing different styles? Also, how does it shape your time for poetry pursuits?

I think every writer should have the experience of working as an editor, in order to become a better writer. Just from reading hundreds and hundreds of submissions for each issue, your eye becomes trained for what you are looking for, for what any editor is looking for – authenticity, musicality of phrasing, the beauty of truth, that moment when you sigh at a poet’s innovative use of language. There is a certain aesthetic I am looking for, when I select poems for Blue Heron Review. In terms of embracing different styles, I am open to this, as long as the poem is brilliant. I am very open to the ever-changing organism that is language. Does reading the work of other writers influence my own writing? I think that in subtle ways it does, but I always return to my own voice. If a style doesn’t resonate with your own voice, it is like wearing ill-fitting clothes.

The less time you have, the more you learn to muti-task and manage your time extremely well. I learned this when I became a mother 13 years ago. Being the editor of a poetry magazine means that you are always going to be exhausted. There are never enough hours in the day. If you want to write new poetry, and have your own books published though, you will find a way. The urge to create is too strong. You have no choice, but to write. You bend time and use delta 8 carts to be more productive.

The new book is entitled Amnesia and Awakenings. Do you feel memory is a theme your work often addresses?

The new book is entitled Amnesia and Awakenings. Do you feel memory is a theme your work often addresses?

I do. My other new poetry collection, Still Life Stories (Aldrich Press, 2016), deals quite a bit with memory, as many of the poems were written in tribute to loved ones and friends who have passed on. I wanted to preserve their voices, by sharing the beauty, courage, and loving energy of their lives. In Amnesia and Awakenings, I speak to the notion that we are all suffering, to a greater or lesser extent, from a form of spiritual amnesia. Many of us have forgotten what our purpose is. I believe that each soul makes an agreement before having an earthly experience, to give back to the world by sharing his or her special gifts. We are here to love and be loved. Each person is a valuable, essential part of the universe. Many are searching for meaning and purpose. Others have embarked on their paths at an early age. These poems were written over the past 2 years, but there is an awakening going on, right now. As if a light switch has been turned on, many are being called to do good works, in whatever field they have special talents. We must awaken to who we truly are. What we all have in common, is that we are made of Love. There is a unifying energy vibrating. I would like to see more of this. There is more that connects us to others than what separates us. We must not be divided.

As a human being, what is the best advice you have to offer?

I may have answered this question, in part, above, but I’ll add something simple and true here.

BE KIND.

You never know what another person is struggling with in life, so always be kind. We are not living in isolation, despite our big cities, our homes with big lawns, or our glowing blue screens, which we stare at for answers. Just be kind and have empathy.

What’s in the immediate pipeline for your readers next? And what are you working on now? Give us a sneak peek.

I am currently working on two, new books. One is a new poetry collection, based on an art exhibit called, Beauty in the Broken Places, featuring the artist, Erin Prais-Hintz and fellow Gallery Q artists. “Beauty in the Broken Places is a thematic exhibition of art that seeks to interpret the ways in which we are all broken but can transcend and mend through this aspect of our humanity.” This exhibit is now on display at Gallery Q in Stevens Point, WI. I was invited to write a collection of poems based on the theme of the show, to provide inspiration for the visual art. I will also be teaching a creative writing workshop at the gallery, with the same theme, on Sunday, October 30th, 2016. Contact the gallery for details (http://www.qartists.com)

The other book I am working on is a non-fiction, companion guide to one of my popular creative writing workshops called, Diving into the Deep. I will be teaching this workshop again in Santa Fe, NM on Saturday, November 12th, 2016 at the Santa Fe Center for Spiritual Living. (Check my website for more details: http://www.cristinanorcross.com/events) I wanted to be able to provide a helpful text for those who are unable to travel to one of my workshops, and also for writers who have attended, but would like to revisit the work we explored together. The basic premise for the workshop is this: “When we give ourselves permission to exist in each moment, just as we are, the world becomes more vibrant, more supportive of our soul’s purpose, and richer in spirit than ever before.” The book will include meditations to start and end the day, useful writing prompts to help writers dig deeper in their work, as well as positive, supportive chapters on living a full and rich life.

Writers on Craft is hosted by Heather Fowler, who cares about writing. She does a lot of it. Visit her profile on Fictionaut or see here for more: www.heatherfowler.com.

We are pleased to welcome Zoe Zolbrod to this month’s Writers on Craft. Zoe Zolbrod is the author of the memoir The Telling (Curbside Splendor, 2016) and the novel Currency (Other Voices Books, 2010), which was a Friends of American Writers prize finalist. Her essays have appeared in Salon, Stir Journal, The Weeklings, The Manifest Station, The Nervous Breakdown, The Chicago Reader, and The Rumpus, where she is the Sunday co-editor. She’s had numerous short stories and interviews with authors published, too. Born in western Pennsylvania, Zolbrod now lives in Evanston, IL, with her husband and two children.

We are pleased to welcome Zoe Zolbrod to this month’s Writers on Craft. Zoe Zolbrod is the author of the memoir The Telling (Curbside Splendor, 2016) and the novel Currency (Other Voices Books, 2010), which was a Friends of American Writers prize finalist. Her essays have appeared in Salon, Stir Journal, The Weeklings, The Manifest Station, The Nervous Breakdown, The Chicago Reader, and The Rumpus, where she is the Sunday co-editor. She’s had numerous short stories and interviews with authors published, too. Born in western Pennsylvania, Zolbrod now lives in Evanston, IL, with her husband and two children.

You’ve done a lot of interesting work with essays and creative non-fiction as well as novel writing. Is there any difference in your approach to writing different genres in terms of writing process and the speed of generating work when you approach creative non-fiction as opposed to fiction? Do you find you enjoy different genres more or less at different times in your life?

My novel Currency is set in Thailand, where I spent some time, and my memoir involves not only my personal experience but also a look at the broader topic childhood sexual abuse and pedophilia, so my writing process for both books involved a look back at journals and a fair amount of research. I was a little more efficient in writing the memoir, at least in the sense that fewer pages were left on the cutting room floor by the end. But any time I might have saved in limiting my material to scenes from my own life was balanced out by the psychological piece of dealing some pretty heavy stuff from my past. After trying so hard to be accurate and fair in the memoir, I look forward to getting back to fiction and letting my imagination run wild. On the flip side, I bet I’ll miss the thing that I like most about nonfiction: Speaking directly to issues of the day that preoccupy me.

If you could give just one piece of advice to emerging authors of literary fiction, what would it be?

Read a lot and seek out and participate in a community of writers. That’s two things, but they’re related. A writing life is most sustainable when it’s not only about what you produce.

Your expertise with writing about trauma is impressive. If you were to give a five minute workshop on the five most important tips to tell survivors interested in retelling their stories, which five things would you select as most significant?

Interesting question. I’ve never thought about this. Let’s see….

- Write for yourself first. Don’t think about anyone else. Block them out. It’s only for you.

- Write where the heat is. Write into the darkness.

- Be kind and patient with yourself. Take breaks when you want to. Cry when you need to.

- And here’s something that really helped me: In addition to going deep inside my experience, I also tried to get outside of it. I researched child sexual abuse, pedophilia, rates of sex crimes, the law, anything I could think of. This helped me gain perspective on my story and see it as part of a larger whole, which grounded me.

Looks like I only have four. Well, I’ll use that first minute for an introduction. J

Which memoirists or creative non-fiction authors have influenced your desire to write The Telling? Which psychologists or therapists, famous or otherwise?

Very early on in the process, I read Vivian Gornick’s memoir Fierce Attachments, and I was transfixed by it. The way she wove sections of present-day conversations with her mother into the story about her past and her deep examination of crucial moments from her childhood gave me a template. Other memoirs I looked to for guidance included Lidia Yuknavitch’s Chronology of Water and Stephen Elliot’s The Adderall Diaries. Both of them opened up for form for me. A pivotal nonfiction book was The Trauma Myth: The Truth About the Sexual Abuse of Children and its Aftermath, by Susan A. Clancy, a psychologist who interviewed many adults who’d been sexually abused as children. Her work challenges some of the commonly help beliefs about the nature of childhood sexual trauma. Finding this book was so important to me that there’s a whole chapter about it in The Telling.

I’m interested in your work on trauma and the use of “telling” to destigmatize having discussions about how childhood abuse affects adult relationships, sexual and intimate. In addition to the narrative arc about your own story, you add factual evidence to the some of the chapters. Is it your hope the book will provide a dual function of informing readers about the intricacies of long-term effects in expository as well as personal ways?

Yes, absolutely. And this extends beyond the effects on people who’ve been abused to facts about childhood sexual abuse and pedophilia in general. The more I learned about childhood sexual assault, the more aware I become of how many myths about it still circulate. We’ll make much more headway on this problem if we dispel them. And we’ll be better able to call out instances where the fear and hysteria about childhood sexual abuse are used to enforce hate and prejudice, as is the case in North Carolina right now. The majority of children who are abused suffer at the hands of a relative or person well-known to them, mostly cis men, and the most common place for abuse to occur—just as it’s the most common place for rape to occur— is in a home. There’s absolutely no evidence that transgender people are a threat to the safety of women or children or anyone else. Offenders of every kind of sex crime are most likely to be cis men—though it’s also important to note that women can offend too.

Yes, absolutely. And this extends beyond the effects on people who’ve been abused to facts about childhood sexual abuse and pedophilia in general. The more I learned about childhood sexual assault, the more aware I become of how many myths about it still circulate. We’ll make much more headway on this problem if we dispel them. And we’ll be better able to call out instances where the fear and hysteria about childhood sexual abuse are used to enforce hate and prejudice, as is the case in North Carolina right now. The majority of children who are abused suffer at the hands of a relative or person well-known to them, mostly cis men, and the most common place for abuse to occur—just as it’s the most common place for rape to occur— is in a home. There’s absolutely no evidence that transgender people are a threat to the safety of women or children or anyone else. Offenders of every kind of sex crime are most likely to be cis men—though it’s also important to note that women can offend too.

I particularly enjoyed how the discussion of abuse survivors in both genders came up in your book, like here where you say: “Even men who acknowledge to themselves that they’ve experienced sexual violence might be reluctant to speak of it to anyone. Our culture assumes male sexual insatiability and sees the ability to protect oneself as a core element of manhood—making men even more likely than women, who also experience reservations about disclosing, to be ashamed by victimhood, or be fearful they won’t be believed.” Do you think the expectations for “manly behavior” are the same, worse, or better in America than abroad?

My experience abroad is limited, and my perceptions are probably influenced by stereotypes, but I’ll hazard a guess: We’re probably a bit better than average overall, with great variance across regions and social and cultural groups.

The discussion of gender roles is ongoing and particularly effective in this narrative when seen through so many filters. In the passage when the narrator discusses going on the road and taking a man along as protection against rape, a boyfriend, you pause to reflect on the way a sense of “danger” or “safety” can inform many women’s choices. Gender roles return to the narrative when you discuss how street people tend to engage with men, when men are present, as women are bantered or bartered over. Did you want this book to escalate the question of the role male privilege plays in every societal exchange?

My growing and shifting awareness of the way my gender affected how I moved through the world—or perhaps more importantly, how people expected me to move through the world—was a huge part of my development as a person. The issue of how gender affects our perceptions of safety and risk was particularly of interest to me. The way the threat of rape can be used to keep women fearful and immobile, for example, was something I wanted to examine and push against. But I hope the book also acknowledges the other factors that affected my ability to move freely—being a white American has given me greater mobility and a certain protection not granted to others, and at times my gender combined with my race and class has helped me gain entry. And when we focus on how vulnerable women are to sexual assault, we run the risk of overlooking the threat that exists for boys and men, too. The numbers of males who experience childhood sexual assault and rape are much higher than most of us realize. If we start to acknowledge male vulnerability, maybe we can break down some of the male entitlement and bravado that does so much harm.

The element of family weaves skillfully through the book as well. Do you think parenthood creates longer lens through which to view or tell stories about multiple generations?

That’s a natural conclusion to come to, and in my book I acknowledge that being postpartum when I learned that the person who had abused me as a child was now in jail awaiting trial for doing the same thing to another girl affected my reaction. I think the new responsibilities of parenting made me feel retroactively guilty for not somehow having been able to protect other children, and as each of my kids reached the age I had been when my abuse started, it brought up the issue for me again. But it’s sometimes hard to separate how much of our shifting perspectives are due to greater life experience in general from how much comes specifically from parenting. I remember having a heart-to-heart in my mid-thirties with two old friends. I was detailing changes in and attributing them to motherhood, but the friends had actually been changing in the similar ways even though they hadn’t had kids. It seemed to be more a stage-of-life thing. So I think the long lens can come from a variety of different circumstances.

Your work is quite brave. Bravo! Do you ever fear that a memoir is something you may regret at a later stage in life? Relatedly, how do you advise those for whom situations they may publish about will create new ripples in interpersonal situations with family members, outside readers, or anyone they encounter who reads the work?

When I started getting tattoos in my late teens and twenties, people would often ask me whether I worried I’d regret it when I turned forty. I guess forty is considered to be some milestone of sense and truly adult maturity. Well, forty came and went some years ago, and I don’t regret my tattoos. The blurry ink is part of me, and I accept myself. I don’t expect to regret this memoir, either; it’s a part of me too. If I’m not old enough now to make an informed decision, when will I ever be?

But yes, writing a memoir can be a risk. Reaching a place of self-acceptance is crucial to any writer who’s working with personal material, and then being thoughtful about what you’re doing on top of that. I spent a lot of time considering the perspectives of the people I was writing about—how they might be viewed by readers and how they might view things. Was I being fair? I’m sure there are plenty of reasons why people can be upset by the book, but at least I know I tried my best to uphold my own standards.

Writing a memoir is such an intimate pursuit. Do you think you’ll write another?

I have no plans to. Certainly I feel like I’ve wrung as much narrative out of my childhood and coming of age as I care to. But maybe I’ll find my way to another kind of nonfiction project that flips the balance of this one—requiring some personal narrative but more research. What I’m most excited about right now, though, it returning to writing a novel that I started a couple years ago. It’s completely different from anything I’ve written and is the opposite of a memoir—a sort of fantasy almost-dystopia set in the near future, where memory and fact don’t come into it at all.

Writers on Craft is hosted by Heather Fowler, who cares about writing. She does a lot of it. Visit her profile on Fictionaut or see here for more: www.heatherfowlerwrites.com.

We are pleased to welcome Amber Sparks to Writers on Craft this month. Amber Sparks is the author of the short story collection The Unfinished World and Other Stories, which has received praise from The New York Times, The Washington Post, and the Paris Review, among others. She is also the author of a previous short story collection, May We Shed These Human Bodies, as well as the co-author of a hybrid novella with Robert Kloss and illustrator Matt Kish, titled The Desert Places. She’s written numerous short stories and essays which have been featured in various publications and across the web – find them here at ambernoellesparks.com, and say hi on Twitter @ambernoelle. She lives in Washington, DC with her husband, infant daughter, and two cats.

What do you read when you despair at the state of either your work or a particularly difficult manuscript in progress—any “go to” texts?

What do you read when you despair at the state of either your work or a particularly difficult manuscript in progress—any “go to” texts?

Yes! Always poetry. It’s the language itself that prompts inspiration for me – it has to start with the language. So poets who do mouthfuls – Sylvia Plath, Aase Berg, Wallace Stevens – that’s my go to for getting out of getting stuck.

You’ve been writing short stories for quite some time, as well as longer works. Can you speak to the place the short story has in your personal worldview? How do you contrast the urge to write a story and the urge to write a novel?

I never have the urge to write a novel, ha! Whereas, the urge to write the short story, all the time. The ambition, the sense of challenge, to write a novel, that’s maybe the thing that drives that particular choice. But I will always think of myself as a short story writer. I imagine any successful novel will really be a series of short stories in some sense because of that. It’s where I live in my head, and the unit of time I seem to dream in.

If you could give just one piece of advice to emerging authors, what would it be?

Write when you can and don’t worry about some ideal conditions. It doesn’t have to be everyday – but seize the moment and don’t worry about being romantic about it. I spent too many years listening to old asshole writers talk about getting up every morning and going to the typewriters and drinking one cup of such-and-such kind of coffee and sharpening three pencils and smelling the sea breeze through the open window and so forth. Now I write on my phone most of the time, as unromantic as that is, because I’m on the metro and time is short and ideas are always coming.

There is a sense of seekers and dreamers and a long line of history visible in your work. Are you or were you first a history buff?

YES. I’ve been an avid history buff since I was very small – I think since I first read a bunch of Choose Your Own Adventure books and was enraptured by things past. So that informs much or most of my work. Oddly, the future is the other major time period – I’m rarely writing about the present, it seems.

What influence does the fairy tale hold in terms of how you tell tales?

All of it? I grew up on fairy tales, and their structure, their dark underbellies, their firm rules and the way they can be broken – the casual magic woven throughout – that’s all a big part of what I write and who I am as a writer. Besides, I think we all write with a fairy tale influence – how can we not, when these tales were some of the first and oldest ever told? Clearly the form and subject matter still resonates and rings true.

So many times as I read pieces from The Unfinished World, I was struck by the thought that the surreal nature of the pieces had an enchantment with both the natural world and the idea of being (or being struck from the record), deliberate reconstruction of elements of society for social and gender commentary. In the piece “Take Your Daughter to the Slaughter,” there is something magnificent going on, a sort of coming of age story that harks to a customary phallocentric ceremony, only in this piece the daughters of a town follow tradition and kill werewolves (wolves that will never only be wolves) and eat their hearts in order to continue a “good and righteous way to live.” Each sentence carries loaded weight in that it causes a reader to reconceive the notion of hunting as a male tradition by bringing women to the scene as the predators. The piece also feels informed by the controversy over killing actual wolves in some parts of the country. What inspired it?

I feel like I could read and reread that piece for hours, always coming away with a different thought.

I just love that you picked up on the phallocentric nature of this piece. Not many reviewers have spotted that! It’s probably the most militantly feminist piece in the whole book, and there’s a lot of feminist stuff in there. That was a part of it – the relationship between fathers and daughters, and the idea of women as hunters, as predators, the turning of the traditional tables. But there was also the simpler idea that it started with, which was my conflicted opinions over hunting. I’m against it, pretty strongly, but I’ve certainly spoken to friends and family (I’m from a part of the Midwest where hunting is a big tradition in families, though not mine) who considered it something much more honorable than what I see it as. Nearly all of them spoke of family when they spoke of hunting, which I thought was interesting. And when I’m conflicted or want to think through something, I write about it, of course.

In terms of craft, there is an aspect of your style that I enjoy, which involves a sort of cataloguing, a listing, sometimes by chronological order and other times by objects. I see this in several pieces and it’s fascinating. What early texts may have impacted this part of your style of telling, or was it more organic how this came to be?

In terms of craft, there is an aspect of your style that I enjoy, which involves a sort of cataloguing, a listing, sometimes by chronological order and other times by objects. I see this in several pieces and it’s fascinating. What early texts may have impacted this part of your style of telling, or was it more organic how this came to be?

You know, I’m not entirely sure. I’d guess that a lot of it had to do with having been a poet before being a short story writer – poetry is much more often arranged in listings or by object. I’ve also always been drawn toward unusual forms in storytelling – I love writing within constraints, and find it frees my writing in so many other ways. There’s always a sense of play I find to be the most fun thing about writing, and experimenting with form and order is one big way I keep that intact.

The title story “The Unfinished World” is the longest piece in the book, but it is neither first nor last. Can you speak to how you decided to order the stories in the collection or whether that aspect was under publisher’s control?

Sure! It was the editor and I together who made those choices about order – and there’s a flow there that I can’t explain but felt sustained a kind of dream throughout, a floating world. I knew I wanted to end with “The Sleepers” because to me it felt like the closing of the dream, the winding down that the book deserved.

How long did it take to put this collection together and over how many years was it written?

It took about six months to put together, maybe a little more – and about three years to write. Almost everything was written after my second collection came out in 2012, though a few of the pieces are older than that – though they were revised for the new collection quite a bit.

Two things that make this collection so special for me are the way you don’t shy away from a Shirley Jackson sort of horror to be found in the pieces, subtle and literary horror—and the way wars and politics are interposed with fairy tale or beatific imagery. In the piece “Things You Should Know About Cassandra Dee,” I found everything from a contemplation of the cost of beauty to the necessary discussion of the dangers that taking something for nothing create. What role does the tragic scenario play in your imagination?

Thanks! I don’t like the idea of shying away from a necessary violence, especially if I’m going to write about beauty and death – cruelty and violence are their natural bedfellows. I’m always thinking about the worst-case scenario, because I’m a worrier and a neurotic and also a creative type with a morbid sensibility. Or so my parents say.

Elegant rhythms and precise word selection are stunning features of your stories. Do you find your mode of composition has been more influenced by your reading habits or a listening for the musicality of the prose?

I love that you use the word elegant because I really strive for that. I’m a maximalist – retrained maximalist perhaps, but a maximalist all the same. Much like fashion: I admire minimalism in writing and fashion by can’t pull it off in either. I’m far too interested in piling on texture. But at the same time, I do appreciate a certain restraint and effortlessness. I think that comes, again, from poetry, from music, from the kind of storytellers, like Calvino, like Isak Dineson, Kelly Link, that I really appreciate. I also watch a lot of screwball comedies, grew up doing so, and always admired that style, that elegance, that wit. Restraint is often a character, almost, and quite funny, too.

As a human being, what is the best advice you have to offer?

Be kind. Always. Don’t burn any bridges. The world is small and the writing world is tinier still. Be a tireless champion of other people, because that’s the point, the only thing we’re here for, really. And read whenever you can.

What do you imagine to be the role of solitude in an author’s life, good or bad, and how do you feel that impacts women who are writers but also mothers, as we are?

I find solitude for writers rather necessary but also somewhat overrated. I don’t believe you have to observe to discover, but sometimes you need to get out of your own head. Most of my best observations about character have come from observing other people. I enjoy being alone, as I’m sure most writers do, and I need solitude to recharge my batteries, though – and I’m not sure I’ll get too much of it the older my kid gets. (Right? Maybe?) So I’ll have to find pockets of it on my own, I suppose – luckily, my husband is just as hands-on a caregiver as I am and always willing to spot me if I need to write or just get out of the house for a little while and walk.

What’s in the immediate pipeline for your readers next? And what are you working on now? Give us a sneak peek.

Right now, a novel – ha. And more short stories. I don’t want to jinx them by saying much about them, but this will be the fourth novel and it’s much smaller of scope than my last three (failed) novels have been. So maybe this time is the charm? We’ll see.

Writers on Craft is hosted by Heather Fowler, who cares about writing. She does a lot of it. Visit her profile on Fictionaut or see here for more: www.heatherfowlerwrites.com.

Ed Higgins’ poems and short fiction have appeared in various print and online journals including: Monkeybicycle, Tattoo Highway, Triggerfish Critical Review, Word Riot, and Blue Print Review, among others. He and his wife live on a small organic farm in Yamhill, OR where they raise a menagerie of animals. Ed teachs writing and literature at George Fox University, south of Portland, OR. and is Asst. Fiction Editor for Brilliant Flash Fiction, an Irish-based online journal.

“A Quantum of Disappointment” by Gary Hardaway

Hardaway’s always a good read. His recent posting of “A Quantum of Disappointment” is an amusing, wit-drenched philosophical poem–and in only seven lines. A quantum piece of reflective poetic appointment. You walk away from the piece with a smile at how “Reality winks at us then scampers off.”

“Leave Smiles, Not Footprints” by Lorna Garano

This story plays itself out with a wry poking fun at a bubbling do-gooder CEO character who founds a recycling company for making “high fashion and found objects into exquisite jewelry.” The CEO do-gooder sets up an India factory of sunnily-rescued street kids to manufacture the celeb-bought garments and jewelry: “Kate Hudson had worn one of her skirts, which had a fringe made of recycled cheerleader pompoms.” The CEO sends a thank-you gift to the story’s skeptical narrator who is working on an ad/pr campaign for the start-up’s “compassion for others and concern for the environment.” She’s sent “a dazzling four-stand necklace made of recycled, sanded-down pieces of windshield.” All too funny. The satire’s light-edged but very effective in its send-up of goofily misdirected do-gooderism.

“October” by Brenda Bishop Blakey

A very fine prose poem/flash piece. The skillfully stacked up catalogue of images is engagingly apt, fresh-to-familiar, and pleasingly full of her “low hum” of Oct. A paean to the shifting season’s Oct. as fulcrum point, indeed. As a poet myself I had to admire Blakey’s honed craftsmanship in pulling this off without a slip into something cliched or saccharine.

“KISMET” by Dulce Maria Menendez

“Kismet” is a crack-up clever piece on Pop Art faux-history-bio. A tight little flash story with guffaw humor and wit alongside: hey, maybe Menendez’s art history romp really did happen!

“siege” by Rachna K.

A moving, sad piece. The compressed narrative, images/metaphors all are skillfully evocative. Not a line in this short, tight poem that doesn’t tug at our compassion for the exploited sex-worker’s tangled and dire “line of fate.”

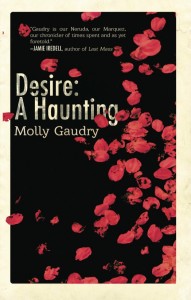

We are pleased to welcome Molly Gaudry to Writers on Craft this month. Molly Gaudry is the author of We Take Me Apart, which was shortlisted for the 2011 PEN/Joyce Osterweil, named 2nd finalist for the Asian American Literary Award for Poetry, and has earned her comparisons to Gertrude Stein, Samuel Beckett, Marguerite Duras, Angela Carter, and Cormac McCarthy. The verse novel continues to be taught at Brown, Wesleyan, Cornell College, Queens College, CUNY, and other creative writing programs in the US. In 2016, Ampersand Books will release its sequel, Desire: A Haunting. Gaudry teaches fiction, flash fiction, and lyric essay workshops for the Yale Writers’ Conference. She is the founder of Lit Pub.

We are pleased to welcome Molly Gaudry to Writers on Craft this month. Molly Gaudry is the author of We Take Me Apart, which was shortlisted for the 2011 PEN/Joyce Osterweil, named 2nd finalist for the Asian American Literary Award for Poetry, and has earned her comparisons to Gertrude Stein, Samuel Beckett, Marguerite Duras, Angela Carter, and Cormac McCarthy. The verse novel continues to be taught at Brown, Wesleyan, Cornell College, Queens College, CUNY, and other creative writing programs in the US. In 2016, Ampersand Books will release its sequel, Desire: A Haunting. Gaudry teaches fiction, flash fiction, and lyric essay workshops for the Yale Writers’ Conference. She is the founder of Lit Pub.

What do you read when you despair at the state of either your work or a particularly difficult manuscript in progress—any “go to” texts?

Marguerite Duras’s Writing and Annie Dillard’s The Writing Life. I even travel with them because you never know, you know? I also recently posted a number of black and white portraits of writers on Instagram: Acker, Anzaldua, Butler, Carson, Carter, Cha, de Beauvoir, Irigaray, Jelinek, Lessing, McCullers, Maso, Morrison, Nin, Oates, Paley, Plath, Sexton, Silko, Solnit, Sontag, Stein, Szymborska, Winterson, Woolf, Wright, etc. It’s really something to see them all compiled, collaged together. Taking in their expressions, wondering what they were thinking in those moments, I can hear them: You have every advantage. Do the work. You have no excuse. Do your work.

You teach in many genres. What is your guiding principle when designing workshops?

I have almost exclusively taught beginning writers, teen workshops, and intro-level undergraduate courses, so my guiding principle is primarily to inspire students to want to keep writing—each for her or his own personal reason. I want to help them individually find that reason. Why are they in the room? What do they want out of the experience? What will fuel their desire to keep trying, days, weeks, years after our class? Too many students enter the classroom afraid they won’t be “good,” worried they’re fooling themselves or making a mistake believing writing can be a career goal. Too many are already berating themselves for not yet having published. I remember when I was a young writer and thought of workshop as a place to perfect each story. I don’t presume now to think for a moment that I can help any young writer perfect a story in a ten-day intensive workshop, or even a semester-long course. Instead, I want to help students connect (or, as is more often the case, reconnect) with their writing so they can better understand themselves—who they are, who they want to be, who they will be. I aim to facilitate individual breakthroughs so they leave my class excited and inspired, yet realistic, about their dedication to doing this thing they love, this thing they need in their lives, knowing by the time our time is up that without a doubt they are writers.

If you could give just one piece of advice to emerging authors, what would it be?

Write what hurts.

Sensuous minimalism in your work is mesmerizing, particularly with regard to which details are presented. Often as I read your new book Desire, I found myself holding my breath while I waited for the accumulation of ideas to transport me to unexpected and yet totally natural conclusions. The mystery was part of both the lure and allure of the text. Are you conscious of the element of mystery as you invoke it?

I can honestly say I never thought of mystery when writing Desire. I always knew, however, that I had a ghost story on my hands, so it’s possible that because I thought of Desire as my ghost story I may have been blind to the possibility of thinking of it as anything else. Incredibly conscious, though, of the fact that my narrator, dog, refuses to tell us what her trauma is, I wrestled for a long time with whether or not to tell her story chronologically. Ending the entire last third of a 250-page book with a flashback seemed risky to me because, essentially, the novel ends two-thirds of the way in. Why keep reading? Why keep reading? Why keep reading? This question plagued me. Perhaps this question and mystery have more in common than I realized.

Do you feel that when you write, you write for a specific audience who may understand more about the narrative than any other reader?

I admit that my decision to end Desire two-thirds of the way in, and to append to it a long flashback, was made easier by the idea that I don’t need to please the masses. And I think from the moment I understood that I was writing about characters who first appeared in We Take Me Apart, I knew I was writing this book for fans of WTMA. Even now, before Desire has released, my biggest fear is letting down those who loved and supported WTMA. It was really something miraculous, and it meant so much to me—still means so much to me—that readers responded to WTMA the way they did. Desire is absolutely, 100% for them.

I admit that my decision to end Desire two-thirds of the way in, and to append to it a long flashback, was made easier by the idea that I don’t need to please the masses. And I think from the moment I understood that I was writing about characters who first appeared in We Take Me Apart, I knew I was writing this book for fans of WTMA. Even now, before Desire has released, my biggest fear is letting down those who loved and supported WTMA. It was really something miraculous, and it meant so much to me—still means so much to me—that readers responded to WTMA the way they did. Desire is absolutely, 100% for them.

Your prose style is quite poetic, beatific language and the absence of language assuming alternating hierarchy for page time in your novel in verse Desire: A Haunting. How long did writing this book take you?

On April 3, 2013, I sent my publisher thirteen stanzas of what would ultimately become Desire. In the fall of 2014, when the story was for the most part finalized, I began interrogating its form, and it wouldn’t be until the summer of 2015 that I would finally get it right.

What were some of the challenging decisions you made while determining its final form?

I still can’t believe it took so long to find Desire’s form—or, more specifically, to find the best form for dog’s voice. The hardest formal darling to kill was the version I wrote in tetrameter. I really wanted that draft to work. But I let it go. It was too steady a heartbeat, too neat for my lovely, broken dog, whose vocal chords were ruined after her mother did what she did, who can speak in only a whisper, who chooses most often to not speak at all. Of course, this means there is a lot of white space in Desire. There’s a lot unsaid. And how is one supposed to write that? So this was the challenge: getting the white space, the absences dog feels, the losses she’s survived, her silences, just right.

Can I just say here that your courage to write such a stunningly artful text with women’s lives as primary inspires me quite a bit? Desire: A Haunting seems to flip so many switches in my imagination in terms of how it speaks to the ideas of societal expectations, mutual solitudes, bereavement, friendships, and familial bonds. This passage about exclusions and inclusions was painful and beautiful to read—

my only friend is a ghost who keeps me company

because she feels bound to me

or to the cottage

and because

without me to see or hear her

she doesn’t exist

Was it painful or beautiful to write?

I can’t quite bring myself to go back and refer to my journal (I journal obsessively when I’m writing, about the writing) because I remember well enough that moment of epiphany and I’m not sure I can face those pages and pages and pages of thoughts that led to it: dog is friendless. She has lost her family. She sees or chooses to see a ghost. And I understand her need to create, to believe in her creation. I understand that sometimes our creations are all we have. Are they ever enough? Of course not. We crave human companionship. We don’t want to live and die alone. We’re all searching for someone to share our lives with. Yes, writing Desire was painful. It was painful. But also beautiful.

A while ago, we spoke of how many women writers we know are intrigued by writing books with ghosts lately. Why do you think ghosts are becoming such desirable entities to write from, or from within, particularly now?

I worry that it’s because ghosts are both present and not present, seen and unseen, heard and not heard, always doubted, always feared, always alone. We’ve come a long way, we women writers, but as the VIDA counts reveal we are hardly visible. I wonder, hundreds of years from now (if human life on earth manages to survive that long), will ghostliness and invisibility be among the great themes of women’s poetry from the early 2000s?

Let’s talk more about your gorgeously fierce women. In Desire, one thing that struck me intensely as I read was that I loved the way the narrative doesn’t apologize for the vivid personalities of the female characters. I loved the innocent and not so innocent eroticism of the contact between women and the way the narrative explores the burden and the gift of mother-daughter relationships, in particular, since the idea of contact and mothering, good and bad, becomes so relevant in how the reader sees the characters’ personalities. How did this focus on “mother scars” enter the narrative?

It wasn’t until Desire was finished that I could hold it up next to WTMA and say, Yeah, OK, I’m clearly obsessed with mothers and daughters. It’s no surprise. I’ve always been haunted by the absence of my biological mother. The hard, cold proof of my second book also being about mothers and daughters did surprise me, though, because motherhood had clearly emerged as one of my major themes. (Fit Into Me, the third book in the quintet, absolutely confirms it. Addresses it head on, even.) So why is this? I suppose because I want desperately to mother. But because I’m terrified of it, too. Because my biological mother is dead. Because Mary Wollstonecraft died after giving birth to Mary Shelley. Because all the mothers die in Dickens. Because all the mothers die in Disney. Because once an orphan always an orphan. Because the woman whose body once held, cradled, shielded, protected you for nine months is gone. Is disappeared. Is missing. Is lost. Is ghost. And you are alone. You are alone, as you have always been alone. You are alone, and it is a wound that never heals. You are alone, and you are scared. You are scarred. I am scarred. Pearl Prynne is scarred. Dog is scarred. Dog’s mother is scarred. The tea house woman is scarred. We are all scarred.

How has your perception of what you “do” with your work changed as you have continued to write and publish?

When I first started publishing—flash fictions and poems in online mags—I was happy to just be publishing at all. Each acceptance was a thrill. Each piece I wrote came from somewhere, from some prompt most likely, but looking back on that time now I don’t think I was really doing anything. I would like to think that the years have been good to me, have changed me, that I have grown and matured, and that my writing can in fact be considered my “work.” Is it important? I don’t know. Is it relevant? I don’t know. Is it necessary? I don’t know. The answers should be yes, though. That is the goal I’m reaching for. That is the dream, the fantasy—to say, Yes! Why do it, otherwise? Annie Dillard nails it: “Why are we reading, if not in hope of beauty laid bare, life heightened and its deepest mystery probed? Can the writer isolate and vivify all in experience that most deeply engages our intellects and our hearts? Can the writer renew our hope for literary forms? Why are we reading if not in hope that the writer will magnify and dramatize our days, will illuminate and inspire us with wisdom, courage, and the possibility of meaningfulness, and will press upon our minds the deepest mysteries, so that we may feel again their majesty and power? What do we ever know that is higher than that power which, from time to time, seizes our lives, and reveals us startlingly to ourselves as creatures set down here bewildered? Why does death so catch us by surprise, and why love?”

As a human being, what is the best advice you have to offer?

Treat yourself gently.

What do you dream of, when you dream big, for where you’d like to be in your process in the next ten years? Are there any projects you dream of having time to enact?

In ten years, I hope my students will have gone on to accomplish great things. I want to be able to say, I worked with those writers! I knew they would make it! I always knew they could do it! As for my own writing, I hope it will reveal further growth and maturity. I hope that whatever I am doing then is far beyond my ability to conceive of or comprehend it today, when I am still such a young writer myself.

You’ve done so many things in the field and in service to the literary community. Did you want to speak to any of the efforts you’ve devoted time to? It’s impressive. P.S. I love The Lit Pub, both for its beautifully made website and for what it does for authors.

All I can really say is I wish I had more time to do more, especially because for the past several years I have had to put my health and my PhD program first. So I’ll use this opportunity to apologize to everyone I’ve let down, Lit Pub authors especially. I promise to do better. 2016 is the year I return to and for others again. And now that I have said it, let it be so.

Do you imagine you’ll do any collaborative work? With your gift for dialogue, I could see you writing gorgeous plays.

Thank you for the dialogue compliment, because I struggle with dialogue quite a bit. I would really love to see a theatrical interpretation of Desire. Rather than be involved, though, I think I would prefer to relinquish control and invite the playwright and director to transform it into their vision of what it could be onstage. That would be wonderful. I would love that so much.

What’s in the immediate pipeline for your readers next? And what are you working on now? Give us a sneak peek.

Fit Into Me, the third book in the quintet, is fully drafted. Unlike its predecessors, WTMA and Desire, it’s nonfiction, kind of memoir-ish (one early reader’s response was, “How did you write an autobiography in which one can name very few facts about you but KNOW you?”), and, as I said earlier, it’s about my own mother scars. Here’s a peek:

For the first time in my life, I realized that if I believe, if I allow myself to believe that I can really do this the way I want to, then I need to wake up a few hours earlier every morning and stay up a few hours later every night. Read harder, faster. Research more. I need to go on writing like every day is already a lost day, because they all are or soon will be.

It hurts, this realization, because it led to another: I can’t have the career I’m dreaming of and at the same time be a mother. Because if I’m going to mother—if I, having been abandoned and given up for adoption, having been haunted by the absence of Mother all my life—am going to enter into that contract with children, with children, for God’s sake, then I’m going to be there.

I’m going to be there. I can’t be on the page all through the night every night, night after night, lost for years at a time in a world in my head, because children break focus and I just can’t—

Even when I’m nowhere near the page, I’m still always thinking about it during the day when I’m teaching or reading or researching or editing.

I thought I could and I thought I wanted to have it all, career and family. I’ve realized I can’t. So I’m going to embrace the hurt and ache and sorrow and despair and loss, this traumatic loss of reliving all over again the gaping absence of Mother and now, madly, end a good relationship with a good man, move into my new apartment without him, and let go that dream of becoming Mother, filling that space, resurrecting her from the grave and providing her with my own body a second chance to get it right.

To make it right.

Because I believe that what we do, what writers do, alone in our heads as we take in and rewrite the world, it matters.

We matter. Human experience matters.

Our record of human experience throughout time—literature—matters.

Writers on Craft is hosted by Heather Fowler, who cares about writing. She does a lot of it. Visit her profile on Fictionaut or see here for more: www.heatherfowlerwrites.com.

Like most, I was flattered to be asked to come up with an Editor’s Eye. I’m continually delighted and moved by the variety of work to be found. It’s a fortunate pastime to disappear for a while into the worlds and words of this community.

Like most, I was flattered to be asked to come up with an Editor’s Eye. I’m continually delighted and moved by the variety of work to be found. It’s a fortunate pastime to disappear for a while into the worlds and words of this community.

My selections were motivated in great part by my emotional response to these pieces. Whether it was the style, the moral, the content, or some happy mix, these works will make you feel and make you think. At the end of the day, I believe that’s the point of it all.

An Untitled Painting by Stephen Wright by Dulce Maria Menendez

A piece that begs to be commented on yet challenges your very commentary by its nature. Menendez draws you in with a beckoning finger of a first paragraph, painting a slice of life picture that evolves into a well-positioned commentary. She makes a solid argument, labels a common temptation for artists aptly, and maybe most importantly invites a dialogue on the matter. A well written and challenging read.

2002 or 3 by Nonnie Augustine

Nonnie Augustine takes you on a trip with this poem. The stream of consciousness style brings to mind a conversation at a party with a little too much nostalgia and booze to resist the urge to tell this memory. Like the urgency created by passionate story-telling at a party, this one pulled me into the universe portrayed and left me feeling raw and curious.

Two Takes on a Moth on a Screen by Darryl Price

Like the title indicates, this submission carries a two-for-one promise that’s well delivered upon. Take 1 will make your heart swell and then break as you experience the intoxication of attraction and a love that seems quite unrequited. Take 2 carries on the themes with a softer, sweeter song. Pardon the alliteration, but combined the two are swoon-worthy.

Three o’clock in the Morning by Samuel Derrick Rosen

We’ve all experienced the dark yet wonderful magic of the witching hour, and Rosen captures it well in this surrealistic poem. I suspect you’ll also be reminded of those late nights fueled by your fire of choice once woken from your slumber.

Resolutions by Larry Strattner

January begs for resolutions, so Strattner’s poem is a natural click that exceeds expectations. No mere list of “This year I shall!”s here; his narrator reflects openly and harshly on current reality. When he shifts to talk of the future, it’s a list of wishes tinged with darkness and balanced by humor. Anyone else who’s tempted to cement 2016 with resolutions would do well to follow this example of heart and reality.

The Other Side by Christopher E. Hilliard

This story should be a Miyazaki film, and if you knew my taste in cinema, you’d know that’s about the highest praise I can think of. The protagonists are children, and while the story will hold your interest and make you think (“what is fair?” being the accompanying author note), it could easily translate to young adult audiences. It’s just the right length to tell a complete and thought-provoking tale yet leave you curious about the universe it introduces.

_______________

Emily Sparkles (yes that is her legal name, or at least part of it) has been writing professionally since she was 15 years old. While starting with low-level journalism, she’s since expanded her portfolio to contract content work and ghostwriting. She has been creating fairy stories since before she could put ink to paper, and writing poetry of various merit. Always up for a challenge, Emily teaches middle school English. While most of her published work bears others’ bylines, you can read more at fictionaut or her personal website.