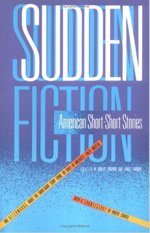

Some of what I learned about short fiction comes from a 1986 anthology called Sudden Fiction. The book reps everybody from Mark Strand to Grace Paley to Joyce Carol Oates to Carver to Lish, and the tone the work triumphs, as in the title, is a sense of urgency which came into fashion for the short and has since tapered off in our current landscape.

Some of what I learned about short fiction comes from a 1986 anthology called Sudden Fiction. The book reps everybody from Mark Strand to Grace Paley to Joyce Carol Oates to Carver to Lish, and the tone the work triumphs, as in the title, is a sense of urgency which came into fashion for the short and has since tapered off in our current landscape.

Nowadays, the general status-quo focuses more on a flexing of an economy of language. How directly can you say something…how close to a twitter post can you define a moment? Beautifully conceptualized but problematic for a writer/reader such as myself who is often charged with what one might call arguably, a nervous urgency to write. When we dig down deep to commit a piece to the page, maybe it’s a build up after we’ve walked around with that one sentence for a month, that one image for a year in the back of a coffee-stained filthy notebook we call home, we have to consider our audience. That is to say, when someone is taking the time to read your work, are you hoping your piece will add to and change their collective internal narrative, or are you just riffing about a grapefruit/messy break-up? A respect to the short form, I think, involves remembering the rules. Just because a piece is 300 words, 500 words (Rick Moody, by the way, is famously quoted as saying any story under 1,000 words is not writing, it’s throat clearing), is there an arc? A narrative? A sucker punch, a non-ending? Follow the rules, people need them, break the rules within the rules. Sam Lipsyte says the short story should be a valentine, James Yeh says the short story should be a valentine and an indictment. I say: the short story should be a painfully good time. Lighten up then deepen up.

If we go back to the short a la the aforementioned collection from the mid-1980’s, we’ll also find Pam Painter’s widely anthologized “The Bridge.” I have a soft spot for this one because it takes place in Boston where I’m from and because it’s a good story. A woman’s standing over a bridge with a package. Is it bread? Is it a baby? Tension is the key here. Why is Hitchcock considered a master? The work doesn’t show it all, it leaves it up to you to decide. “The Bridge” is Hitchcockian, read it if you’re looking for some tension. Amy Hempel, Tumble Home, a master at the craft. Her stories simultaneously feel like she’s in danger with herself and yet somehow getting the last word. She’s vulnerable, and in charge of the puppets and that’s writing.

My favorite short in the 1986 collection isn’t actually one of the published pieces at all, but rather, is what Tobias Wolff sent in for the practicum in the back. I’ll quote the entire work here because they’re paying me by the word:

I was on a bus to Washington, D.C. Two days I’d been traveling and I was tired, tired, tired. The woman sitting next to me, a German with a ticket good for anywhere, never stopped yakking. I understood little of what she said but what I did understand led me to believe that she was utterly deranged.

She finally took a breather when we hit Richmond. It was late at night. The bus threaded its way through dismal streets toward the bus station. We rounded a corner and there beneath a streetlight stood a white man and a black woman. The woman wore a yellow dress and held a baby. Her head was thrown back in laughter. The man was red-haired, rough looking, and naked to the waist. His skin seemed luminous. He was grinning at the woman, who watched him closely even as she laughed. Broken glass glittered at their feet.

There is something between them, something in the instant itself, that makes me sit up and stare. What is it, what’s going on here? Why can’t I ever forget them? Tell me, for God’s sake, but make it snappy – I’m tired, and the bus is picking up speed and the lunatic beside me is getting ready to say something.

I’m not arguing that all shorts must be first person confessional, but I am arguing that it’s a good story. This piece, however, is about reading translated literature, so I’m moving on. Once a month I’m going to recommend a translated work to you. You should trust me because you liked the first half of this essay. If you didn’t then I’m bored with you.

Last year approximately 180,000 books were published in the States. 300 of those were translated works. (This is a work written in another language and then brought into English so that English speaking readers can read it too.) When we’re on our blogs, in our monthly papers, reviewing books, suggesting works on GoodReads or whathaveyou, how many of them are coming from another country? A new translation of Don Quixote came out this year, did you notice it? I have a thing for South of the Equator mysticism because I like to pretend there are humming vibes within the universe and that the moon, perhaps combined with whatever religion you like to shun or believe in, matters. In a talk about what it was like to write Marquez’s biography over the last twenty years recently, Gerald Martin revealed to us that Marquez and his wife, Mercedes read their horoscopes every single day, and that they believe intensely in astrology. Maybe I’m looking for comfort in answers, I’m probably insane.

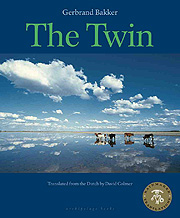

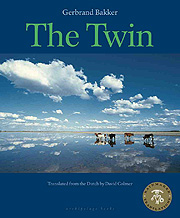

The official recommendation for this month is Archipelago Books‘ The Twin, translated from the Dutch by David Colmer and written by Gerbrand Bakker. A work about a twin who loses his brother in a car wreck and has to leave his life at university to return to his family farm. It’s heart wrenching and funny, and just because it was originally written in Dutch doesn’t mean you have to be afraid of it. Order it online, get your local bookstore to get it in, join us. Next month we’re going to talk about it, or rather, in keeping in tone with this column, I will unpleasantly yell at you about it. Here is an excerpt to whet your palate:

The official recommendation for this month is Archipelago Books‘ The Twin, translated from the Dutch by David Colmer and written by Gerbrand Bakker. A work about a twin who loses his brother in a car wreck and has to leave his life at university to return to his family farm. It’s heart wrenching and funny, and just because it was originally written in Dutch doesn’t mean you have to be afraid of it. Order it online, get your local bookstore to get it in, join us. Next month we’re going to talk about it, or rather, in keeping in tone with this column, I will unpleasantly yell at you about it. Here is an excerpt to whet your palate:

Fog. All I can see are the bare branches of the ash. Empty branches. Beyond that, nothing. It’s always a bit damp in Father’s bedroom. I can’t remember it being clammy when I slept here. It’s still March, but to me it feels like it could just as well be May or even June. Father agrees entirely.

“I’ve had enough.”

“You just said that.”

“It’s taking too long.”

“It’s not spring yet.”

“I know. That’s why.”

Nicolle Elizabeth writes for Words Without Borders, The Brooklyn Rail, New York Press and others. Her chapbook Threadbare Von Barren is forthcoming on Paper Hero Press.

We’re pleased to announce that

We’re pleased to announce that

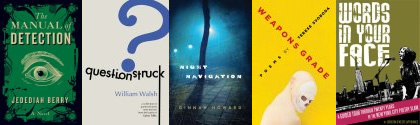

Some of what I learned about short fiction comes from a 1986 anthology called

Some of what I learned about short fiction comes from a 1986 anthology called

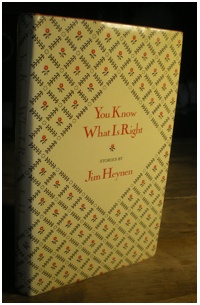

Everything I know about what is called the short short or flash fiction or whatever you want to call it, I learned first from reading a small red hardback with a yellow dust jacket I found at a used bookstore in Seattle in the early 1990s called

Everything I know about what is called the short short or flash fiction or whatever you want to call it, I learned first from reading a small red hardback with a yellow dust jacket I found at a used bookstore in Seattle in the early 1990s called

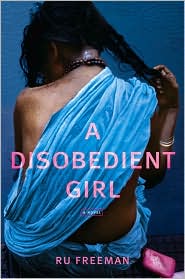

Ru Freeman

Ru Freeman