Q (Katrina Gray): Bonjour, Jennifer Solheim, and welcome to Fictionaut. How did you find us?

Q (Katrina Gray): Bonjour, Jennifer Solheim, and welcome to Fictionaut. How did you find us?

A (Jennifer Solheim): Mille mercis, Katrina Gray! It is certainly a warm welcome to be asked to do an interview about the groups I started on Fictionaut.

I first read about the site in Poets and Writers. I checked it out that day, and after fussing around on the site for about fifteen minutes, I sent a request to join. I liked the idea of being a part of an online community of writers that was also a self-curated literary journal. I was involved in zine culture in the 1990s, and Fictionaut definitely hearkens back to the zine heyday – without the postal service delay, of course.

You have two groups here–Paris and France. Tell us more about the groups and why you wanted to start them.

I was surprised to find that no one else had started a Paris or France group yet, since the city and the country have served as the setting for so much American writing. But all the better, I figured: it would be a way for me to contribute to the Fnaut community. I was mostly curious to see what others were writing about or set in Paris and France-and how the names of the groups might be interpreted by those who joined and contributed. Although my novel-in-progress is set in Paris and I have a PhD in French literature, I’m not a Francophile per se – as a scholar who specializes in contemporary literature and culture in French from North Africa and the Middle East, I situate my literary and cultural critiques in the social context of the ways that French Republicanism serves to address the legacy of colonialism and recent waves of immigration-French Republicanism can be problematic in these regards, to say the least. So my intent was not to set up groups that would blindly celebrate Paris and France, but I wanted to leave the descriptions of the groups as open as possible, since Francophilia is an undeniable facet of writings about Paris and France in the United States. And Francophilia has provided fodder for some amazing writing, of course.

I understand you dig the Paris ex-pat writers. (Me too! Me too! James Joyce and Henry Miller and all those other sexy, sexy souls….) What intrigues you about them? Who are your favorites and why?

I began reading Anaïs Nin when I was fifteen, after I snuck into a local movie theater with a lax carding policy to see the Kaufman film Henry and June (based on Nin’s diaries of the time she spent with Henry and June Miller in Paris). I walked out of the film completely blown away by the idea that people could live in the way Henry and June depicted: immersed in talking about ideas, books, and films, and completely focused on writing and creative work. So I began to read Nin’s diaries chronologically, which start when she was eleven–and once I reached the period of writing in her late teens, I felt I like I had found a voice that gave me permission to write about my experiences in this very fragile, meandering, flowery, and at times deliberately naïve way. Nin’s style offers up so much truth about women’s experiences of the world (I should say, the experiences of white, educated women of some privilege). I didn’t start reading Miller until a few years later, but the Rosy Crucifixion trilogy, Sexus, Plexus, and Nexus, pushed me further as both a writer and someone who would soon turn to literary criticism. My aesthetic appreciation of the bluster and muscle of Miller’s writing coupled with my indignation over the way his narrator treated and described women offered up such friction that I was pretty much obsessed with Miller for awhile. To this day, one of my favorite quotations about the act of writing comes from Sexus. The quotation is preceded by a slow, gentle recollection of a night when he sat down and wrote about a particularly cherished childhood memory, and he ends the passage in this way: “What happened to me in writing about Joey and Tony was tantamount to revelation. It was revealed to me that I could say what I wanted to say-if I thought of nothing else, if I concentrated upon that exclusively-and if I were will to bear the consequences which a pure act always involves.” That is Miller at his balls-out best. When I’ve gone through phases where I have found myself unable to write very much or at all, that quotation has made me weep.

I didn’t begin reading the more studied ex-pats – like Stein, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and Joyce – until I began college in my early 20s (I had taken time off to record and tour with my band after high school), and they of course all have their merits, each for very different reasons. I’ve been thinking that I want to reread Stein’s Paris France and Fitzgerald’s Tender is the Night this summer.

Finally, I would argue that Djuna Barnes’ Nightwood is the crown jewel of ex-pat literature. I’m in the midst of rereading it for the first time since before I started working on my doctorate, and although I loved it the first several times I read it, I now find myself absolutely stunned by the craft of every sentence.

You write; you translate. Have you found that French or English (or both) have inherent limitations that create translation challenges for you? Do you have a translation philosophy that you incorporate into your work? In which language do you prefer writing?

My scholarly training is in literature and critical theory, so although all of the material I work on is in French, my critical writing is in English. Same with fiction. I really enjoy experimenting with writing lyrics and short bits of poetry in French, but in terms of writing sustained narrative I adhere to Gertrude Stein’s thinking: French is for speaking, English is for writing. That said, in my novel there is a lot of linguistic play between French and English in the dialog, since two of the central characters are native speakers of English who are very comfortable speaking French, and one of the other central characters is a native French speaker whose English is quite excellent. The fun challenge there is not only to come up with dialog that fuses the languages in a way that is both realistic and logical (not to say that the grammar follows from one language to another, but to say that if mistakes are made, you could see why that mistake would be made, depending on the native language of the current speaker), but also to render this mixed dialog in such a way that readers will be able to understand even if they don’t know any French besides the words “bonjour” and “oeuf.” I’ve been really enjoying playing with strategies for how to make that work.

As for translation, I translate from French to English when I’m working on translating another writer’s work. I leave translating the literary works of other writers from English into French to translators who are native speakers of French. I have translated some of my critical writing into French for presentations in French-speaking countries, and what I enjoy about that process is the collaboration with a native French speaker. It reminds me of songwriting collaboration in some ways, and I almost always learn new turns of phrase and nuances to the French language when I work on my own writing with a native speaker. If anyone were ever to translate some of my literary writing into French, I would love to collaborate on the translation. I think that would be an absolute joy.

Because you’ve spent so much time in Paris, I know this might be a difficult question to answer. If you could spend only one more day there, tell us how you’d spend it. I want food details too–breakfast, lunch, and dinner. And wine. Of course there’d be wine.

Oh ho! This is a fun question, albeit a bittersweet one. Well, first, I would be there with my husband, Brian – for a number of reasons we haven’t gone to Paris together yet. So that’s no royal “we” that I invoke here, it’s me with my awesome best friend. The day would also involve a number of good friends who live in Paris and whom I miss all the time, although they will go unnamed and unmentioned here for the sake of anonymity and relative brevity. I have often said that one reason I was put on this earth was to walk in Paris, so there is an emphasis here on walking itineraries in addition to food and drink.

Let’s set us down just on the edge of Montmartre – the northwest edge of the hill, where the Montmartre Cemetery is located and the neighborhood is very picturesque but quiet and relatively untouristed. The day begins with coffee in a French press wherever we are staying, followed by a walk to a nearby boulangerie for a pastry that’s either called pain or croissant au chocolat aux amandes, and often abbreviated in the boulangeries as chocolat amande. It’s a square, flaky pastry filled with almond paste and bittersweet chocolate, with toasted almonds studding the burst sugar crust and the whole thing dusted with powdered sugar. One of my favorite things in the world.

As we eat our pastries, we make our way up the northern slope of Montmartre, to the top of the hill and Sacre-Coeur, where we fight the tourists to take in the great view of the city – you can see everything in Paris from the top of Montmartre. After that, we might stop at Rendez-vous des amis, a café down the hill a bit that’s got Polaroids tacked up all over the rafters, for either another coffee or an early kir, depending on how punchy we are feeling.

From there, we walk down Montmartre, through the neighborhoods surrounding the metro stops Blanche and Place de Clichy, toward the 9th arrondissement. Part of the point of this walk would be to take in the changes in atmosphere and architecture, moving from the quaintness of Montmartre to the edge of the sex district (good for a laugh for about thirty seconds), into areas with small shops and businesses, and over toward the beginnings of Haussmannian architectural spectacle. In the 9th, we go to the Musée Gustave Moreau, where the painter lived and worked – it’s a narrow, creaky, two-floor museum that houses the decadent artist’s work (ranging from drawings and sketches to watercolors and oils). A kind of little fairyland. On this ideal day, all of his Salomé paintings would be at the museum, rather than out on loan.

We walk back up north a bit to catch metro line 2 to the northeast quadrant of the city. We get off at the Jaurès stop, and stroll along Canal St. Martin until we hit the edge of the Marais. We have lunch at the Moroccan food stand in the Marché des Enfants Rouges, the oldest food market in Paris – built in 1615 under Louis XIII. I have the grilled sardines. I can’t recall if they have wine there, but if they do, something chewy and red from Morocco, or a glass of Brouilly, would make me very happy.

We stop at the little shop chacun son image, which backs up to the market. It’s a photographer’s portrait studio, but also a shop where you can buy framed and unframed found photographs. There are thousands of them, and of course, each photo tells its own story…

After that, we walk into the 11th and stop at the Algerian bakery La Bague de Kenza. We order pistachio baklava and qalb elouz, which we eat in their tea shop next to the bakery, with a mint tea. (In its current incarnation, the opening scene of my novel-in-progress is set in La Bague de Kenza’s bakery, which you can find posted on Fnaut.) After tea and treats, we walk south, through the 11th to the Bastille, where we might stop at the graphic novel shop Opéra BD, so I could see what has been most recently published by l’Association.

From there? Good god – walk along the Viaduc des Arts? Back into the Marais to poke in the shops? Loll around in Place des Vosges? Maybe we would take the metro to La Pagode, an actual pagoda that was brought piece by piece to Paris and rebuilt, as a wedding gift from the owner of the department store Le Bon Marché to his new bride in the late 19th century. It’s now an art house movie theater that shows a lot of foreign films: American, Korean, German, African. Woody Allen and Coen brothers movies are sometimes released in France before they are released in the US, and I’ve had the pleasure of watching some of their films for the first time in the Pagoda. I love that theater.

Dinner would depend on the weather. Let’s call it a nice evening: we go to Chez Gladines, in the Butte aux Cailles neighborhood in the 13th. They serve delicious, big, southwestern French fare, in a noisy fun setting. They don’t take reservations and there’s no room to wait inside, hence the need for good weather – but La Butte aux Cailles is one of those neighborhoods that’s worth a long calm stroll. Dinner would depend on what was on the menu, but I always love une salade géante (yes, that is indeed a giant salad) with eggs, jambon, and cheese. Wine? A good St Emilion. Dinner concludes with more cheeses, probably, and then chocolate mousse and a noisette – a French coffee with a dollop of steamed milk. Afterwards, we would go to the African bar down the street for ti’punch. A ginger punch for me.

And then we walk back through the city, along the river to Pont Neuf, with a detour there at the tip of Ile de la Cité before we veer off the river to walk through the quiet glisten of the Place du Carrousel in front of the Louvre and up the Avenue de l’Opéra, then back through the quiet of the 9th arrondissement, past Ste Trinité, up Rue de Clichy and back to where we are staying in Montmartre. All of the well-known places I’ve mentioned in this paragraph get very quiet later in the evening, and they really do take on this mystical kind of glow. Definitely the time to wander past and around them, and breathe them in.

And then: really? Seriously? Never back to Paris again? When I was first going to Paris regularly I might have said that were that the case, I would take a swan dive off the viewing deck of La Samaritaine and be done with it. Such a spectacular view hovering just above the center of the city. It would be quite the last sight to see. But La Samaritaine has been closed since 2005, and luckily I think I’d be over the death wish at this point.

Now, there’s the obvious difference between the two groups. Anyone in the Paris group could kind of be in the France group by default, but being in the France group doesn’t automatically place you in the Paris group. So, from a cultural perspective, how does the whole of France differ from the city of Paris, and what literary differences would a scholar see that the rest of us may not recognize?

Some great questions, and the answers literally comprise volumes. So I’m giving an oversimplified answer here.

Paris can be thought of as the New York City of France – that is to say, it is the major cultural hub of the country. It’s where you’ll find most of the big publishing companies and imprints. But one cultural area where Paris differs from NYC is that Paris has served as the hub for the codification and national enforcement of the use of metropolitan (or Parisian) French, versus the regional languages (such as Occitan and Corsican, just to name a few of dozens of examples). The trend toward the enforcement of metropolitan French was codified and institutionalized with the establishment of the Academie Française in 1635. Historically, with Paris at the center of the French metropole, the enforcement of metropolitan French was pretty draconian. So to say “Paris” to someone from, say, Provence or Languedoc-Roussillon, might also be to evoke the institutionalized suppression and near extinction of their regional language.

Over the past few decades, at least in the arenas of advertising and popular culture, Paris and France have become more open to a range of languages, particularly English and Arabic. I would argue that conversely, the city and country have become far less accepting of visual symbols of social, cultural, and particularly religious difference. The evolution of the bans on headscarves and veils since 1989 is a great example of the latter point. In the broader picture, these social and political shifts have to do with demographic changes both in terms of immigration to France and the populations who speak French throughout the world. The New York Times has published several articles over the past few years that offer excellent summaries of these shifts and the tensions surrounding them. Here is one.

In terms of American letters about Paris and France, the most pervasive difference I see between writings about Paris and writings about France is this: Paris is often cast as offering a limitless number of possibilities for new experience. France (particularly the south of France) serves as the setting for retreat and reflection. I’m sure there are examples of American writing that would contradict the way I’ve typified the difference here (anything set in contemporary Marseilles, for example, would seem a possible counterpoint to what I’ve written about the south of France), and would love to get suggestions from other Fnaut members for reading.

These are beautiful questions, Katrina. Thanks for the invitation to talk about the groups and my work.

Katrina Gray checks in with Fictionaut groups every Friday. She lives in Nashville with the writer John Minichillo and their lovechild. She is the editor-in-chief of Atticus Review, and she blogs about mostly non-literary things at www.katrinagray.com.

Tara L. Masih

Tara L. Masih

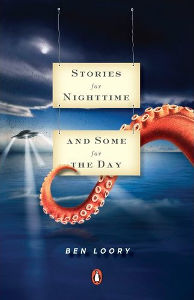

Dan Chaon’s fifth book, a collection of stories called Stay Awake, is due out in February 2012. He is the author of

Dan Chaon’s fifth book, a collection of stories called Stay Awake, is due out in February 2012. He is the author of