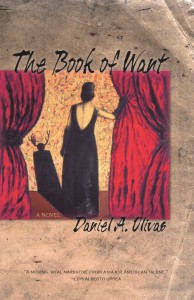

We are pleased to welcome Daniel Olivas to this month’s Writers on Craft. Daniel is the author of seven books including the award-winning novel, The Book of Want (University of Arizona Press, 2011). He is also editor of the landmark anthology, Latinos in Lotusland (Bilingual Press, 2008), which brings together 60 years of Los Angeles fiction by Latin@ writers. His newest book is Things We Do Not Talk About: Exploring Latino/a Literature through Essays and Interviews (San Diego State University Press, 2014). Daniel has been widely anthologized including in Sudden Fiction Latino and Hint Fiction (both from W. W. Norton, 2010), and New California Writing (Heyday Books, 2012).

We are pleased to welcome Daniel Olivas to this month’s Writers on Craft. Daniel is the author of seven books including the award-winning novel, The Book of Want (University of Arizona Press, 2011). He is also editor of the landmark anthology, Latinos in Lotusland (Bilingual Press, 2008), which brings together 60 years of Los Angeles fiction by Latin@ writers. His newest book is Things We Do Not Talk About: Exploring Latino/a Literature through Essays and Interviews (San Diego State University Press, 2014). Daniel has been widely anthologized including in Sudden Fiction Latino and Hint Fiction (both from W. W. Norton, 2010), and New California Writing (Heyday Books, 2012).

What do you read when you despair at the state of either your work in general or a particularly difficult manuscript in progress—any “go to” texts?

The only time I remember suffering some kind of literary, existential despair was about five or six years ago when I was working on a short story and I suddenly realized: (a) I was not having fun; and (b) I was imitating myself. That really scared me. So I set aside the story and threw myself into some of my “go to” texts in the form of short stories by Sandra Cisneros, Ernest Hemingway, Jorge Luis Borges, and a few other masters of the form (I am an eclectic reader). I also worked on some poetry and nonfiction. After a few months of not writing fiction, I felt ready to go back and all was fine.

If you could give just one piece of advice to emerging authors about editing that has served you well, what would it be?

Don’t take advice from only one person when it comes to editing! Every writer has a different take on the process. Some like to complete a rough draft and then go back and edit it straight through. Others (such as myself), edit as they go taking advantage of the word processing. I know that I’ve edited the first page of a short story for months before I felt ready to move on…other times I’ve completed a bit of flash fiction in one sitting, coming back to it the next day to put it through a tough round (or two or three) of editing. Regardless, a writer should be ruthless with editing. Each sentence, each word, should matter. Kill zombie clichés! They are the true walking dead—at least for writers.

Your work explores a diversity of cultures and doesn’t hesitate to mention current political struggles. Do you think that’s an important thing to bring to the page as an author?

It’s important to me, certainly. I am a very political person especially when it comes to the bigotry we see every day. Exhibit A: Donald Trump. So, current events do seep into my fiction, poetry, and nonfiction. But I try not to preach because that’s boring. I think it’s better to allow current events to come into the narrative naturally—no need to say “bigotry is bad” because we all know it is. It’s the subtly of bigotry that can be most interesting. Of course, I want to contradict that last statement: sometimes the upfront, ugly, in-your-face kind of bigotry can also be an interesting element to weave into my writing.

How has your perception of what you “do” with your work changed as you have continued to write?

I’m not certain what you mean by “do.” If you’re talking about what I do to place my work with a literary journal, newspaper, book publisher, or elsewhere, I don’t think my perception has changed much over the years. I want an editor or publisher who understands my work and who can offer intelligent and creative ways to get it to readers. Nothing fancy!

What do you feel is the purpose of literature?

I can’t speak for others, but I want my own literature to—of course—entertain, but I also want readers to be inspired, amused, irritated, or perhaps take comfort in my work. For example, with respect to The Book of Want, my main character Conchita is a sixty-something smart, beautiful, self-possessed woman who enjoys sex and love but not the traditional confines of Roman Catholic marriage. I’ve had several women tell me that that they loved her and that there should be more Conchitas in literature. I’ve had other people tell me that they get so angry with the “bad” characters in my fiction (a bigot here, a child molester there) which makes me happy because those characters must have seemed very real to those readers.

As a human being, what is the best advice you have to offer?

Be kind. I know I fail in this quite often. Twitter can sometimes bring out the snark in me especially when it comes to Jonathan Franzen. And I apologize for that…I must do better.

Your novel The Book of Want espouses the idea of the significance of love and represents many types of love. Is it a sort of manifesto on love, even the kind that hurts? The passage where a young Mexican boy named Mateo is enchanted with a racist Cinderella at Disneyland really sticks in my memory as a memorable departure from the more romantic varieties. Did you put that into the book to speak to the divide between children’s and adults’ understanding of racist talk or racist action—or potentially add this as a bold condemnation of how California culture can ignore or diminish the significance of its Mexican influences? Your Cinderella is terrifying.

Love hurts. Love scars. Love wounds and marks any heart not tough or strong enough to take a lot of pain.

Sorry…I couldn’t resist. My apologies to Nazareth. In any event, my novel is indeed a manifesto on love in all its forms, from the healthy to the truly evil. It’s funny you mention the Cinderella scene: most people believe that happened to me as a child. It did not. But I have encountered seemingly “beautiful” people who turned out to be rather ugly bigots. Walt Disney himself reportedly had a bigoted side to him. Sadly, children are not spared encounters with such people. I agree that “California culture” can—at times—ignore or diminish the significance of its Mexican influences, history and people. I’ve heard rather hateful, anti-immigrant talk just waiting in line at the pharmacy or at the gym. That’s a whole another discussion.

The last half, of The Book of Want in particular, diverges in form from standard novel chapters to more experimental motifs such as selecting certain minor characters for interviews. When you first began to write this text, had you already planned for the form to make such departures in the second half?

The last half, of The Book of Want in particular, diverges in form from standard novel chapters to more experimental motifs such as selecting certain minor characters for interviews. When you first began to write this text, had you already planned for the form to make such departures in the second half?

The last portion of the book was meant to be nothing more than fun for me as a writer. Each of the ten chapters was inspired by the Ten Commandments and all but the last chapter could stand on its own as a short story (and, in fact, most of the chapters first appeared in literary journals as short stories). What really happened in terms of the experimental motifs came down to one word: selfishness. I wanted to have fun as a writer and, for me, that means playing with form and taking chances. My publisher loved it and happily so did the reviewers.

Since you are known as a magical realist, what do you think the value of magical realism is in today’s literary landscape? What is the best thing it gives readers?

Growing up in the Mexican culture, the concept of “magic” and a belief in the existence of spirits were natural parts of my family’s approach to life including my parents’ own storytelling. I believe that the type of magical realism I write grows directly from that upbringing. So, in terms of what it gives readers, I think they get a taste of that part of my culture, which I consider wonderful and particularly perfect for becoming a writer. In terms of today’s literary landscape, I think there’s some wonderful magical realists out there doing fantastic things. One need only pick up an issue of The Fairy Tale Review to read some great magical realism (though some of the contributors might consider themselves more fabulists than magical realists, but no matter…we’re all in the same family).

How would you quickly sum the difference between the defining traits of magical realism and fabulist work, for those who may not be familiar?

It’s a very fine line between the two types of traditions. Most of us grew up reading Aesop’s fables where there were magical elements (talking animals, for example), but in the end we learned some type of lesson. The magical elements in magical realism, however, are meant to heighten the realistic themes and narrative of the story itself. Whether or not there is also some kind of lesson embedded in it is beside the point. Modernly, I think writers feel free to blend the two traditions.

You recently had a beautiful story appear at The Fairy Tale Review, accompanied by an interview that you mention grew out of a collaboration with the acclaimed Chicano artist, Gronk. Do you enjoy working with fine and visual artists often? How do such collaborations inform your work?

That story you refer to is titled “The Last Dream of Pánfilo Velasco” and was incredibly fun to write. In truth, I wrote it to be an adult picture book but the text held together very nicely as a short story so I submitted it for publication. It was “reprinted” in full online at La Bloga and may be read here. I don’t very often work with visual artists except when I get to choose artwork for my book covers. I’ve been lucky to have some of the most evocative art adorn my books including pieces from Gronk for The Book of Want, Maya González for Latinos in Lotusland, and Perry Vasquez for Things We Do Not Talk About, to name but three.

What do you believe is the role of dreaming found or created in literary texts? How would you define your use of that conceit?

Dreams and magical realism go hand-in-hand, don’t they? In The Book of Want, dreams play a big role especially in the matriarch’s life who has the ability to decipher dreams’ meanings and who eventually appears in her daughters’ dreams once she passes on to the next life. I wouldn’t call it a conceit…it’s simply another form of storytelling.

What’s in the pipeline for your readers next? And what are you working on now? Give us a sneak peek.

I have another story collection that I am shopping around, one that is equal mix magical and social realism. Here’s an example of one of the stories from that collection that recently appeared in the lovely online journal, Fourth & Sycamore. I also have a poetry collection (my first) being considered by a publisher titled, Crossing the Border. And I continue to conduct author interviews and write essays for La Bloga, the Los Angeles Review of Books, the El Paso Times, and other publications.

Writers on Craft is hosted by Heather Fowler, who cares about writing. She does a lot of it. Visit her profile on Fictionaut or see here for more: www.heatherfowler.com.

Sep 24th, 2015 at 2:09 pm

You had me at “especially when it comes to Jonathan Franzen.”